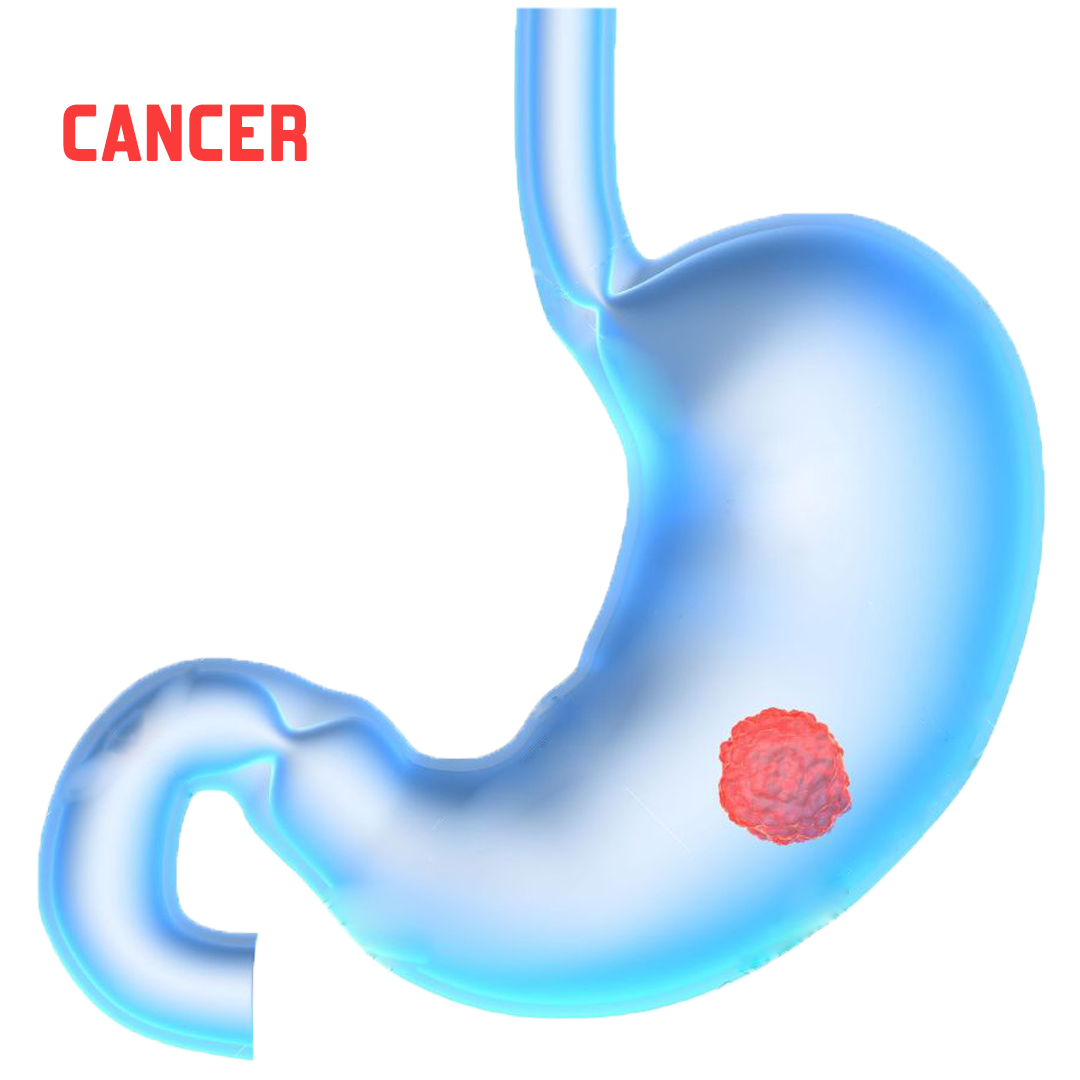

Cancer- Recovery from Surgery

Colon-Rectum Cancer- Postoperative Recovery & Care

Following treatment for either colon or rectal cancer, ongoing follow-up to detect recurrent disease is considered an important part of patient care for colorectal cancer.

Summary: 60 Second Read

Colorectal cancer follow-up refers to a systematic approach to monitoring patients for new or recurrent cancer after treatment.

Colorectal cancer follow-up refers to a systematic approach to monitoring patients for new or recurrent cancer after treatment. The majority of these recommendations apply to both colon and rectal cancers. Differences are noted where appropriate. Adherence to these guidelines can be useful in early detection of pre-cancerous polyps and cancer recurrence. However, systematic follow-up is not foolproof and does not guarantee a new colon cancer will not occur.

Following information is intended to help patients and their families understand their continued risks for recurrent cancer and to help guide appropriate follow-up care to maintain their cancer-free state. Each patient’s care is ultimately evaluated individually. Any questions or issues related to appropriate follow-up on an individual basis are reviewed by the patient’s treating physician, often in consultation with a colorectal surgeon or other specialist.

Patients with a history of colon or rectal cancer need information regarding:

- Which patients need follow-up testing

- The risk of recurrent colorectal cancer

- The types and timing of appropriate follow-up tests

- The signs and symptoms of cancer recurrence

- The risk of developing new polyps

- Increased family risk of polyps and colon cancer

The following information outlines the general guidelines for follow-up after treatment for colon or rectal cancer.

WHICH PATIENTS NEED TESTING?

Once a patient has been diagnosed and treated for colorectal cancer, it is important to understand that continued follow-up is needed. Compared with patients with no history of colon or rectal cancer, patients with a history of colorectal cancer are at significantly increased risk for not only colon cancer recurrence, but also the development of new polyps, which are the precursor lesions to colorectal cancers.

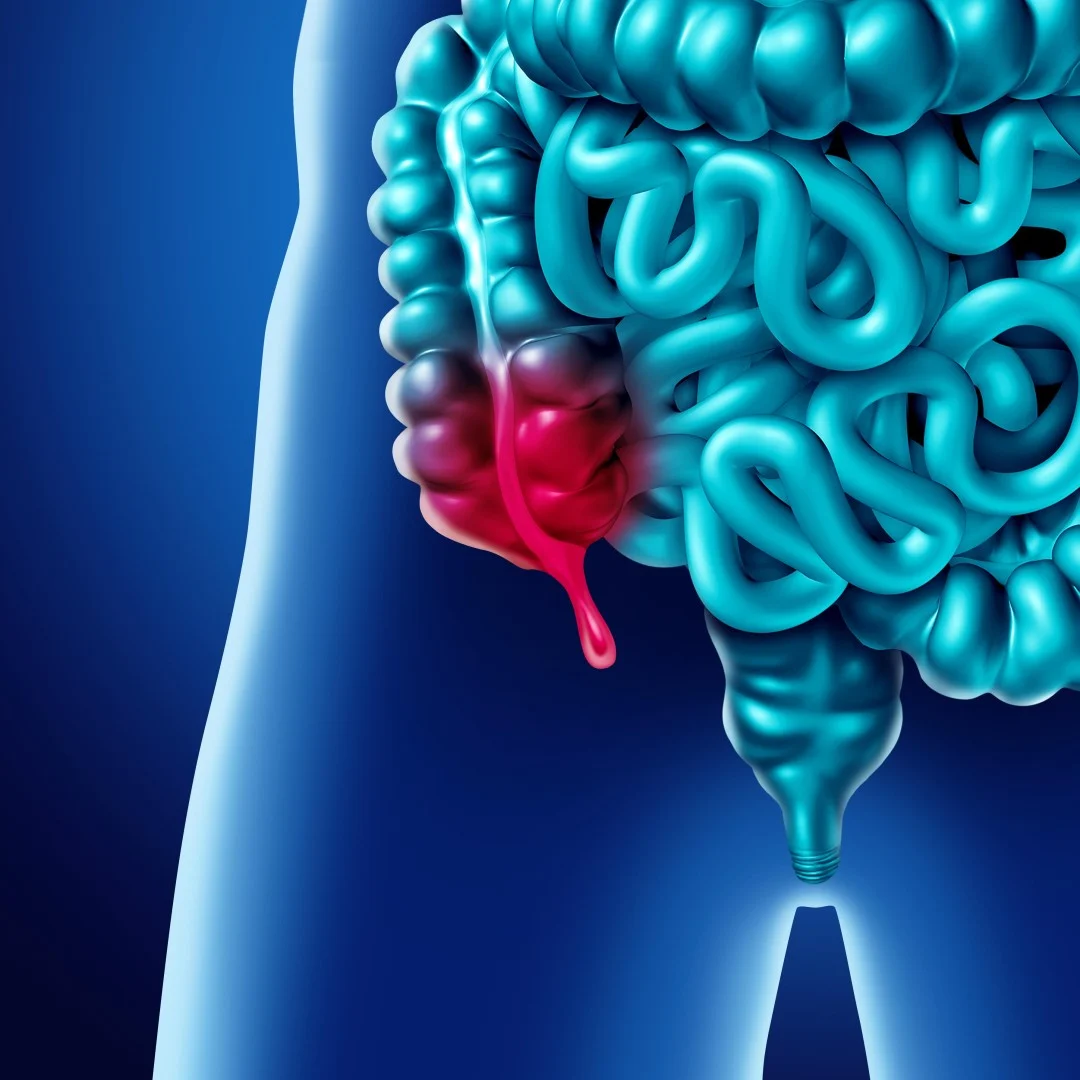

Any patient who has had curative surgery for a polyp or colorectal cancer has approximately double the risk for developing new polyps. These patients need to have their first colonoscopies 1 year after surgery, a follow-up colonoscopy 3 years later, and subsequent colonoscopies at no less than 5-year intervals. If any new polyps or lesions are found, patient surveillance should be modified appropriately.

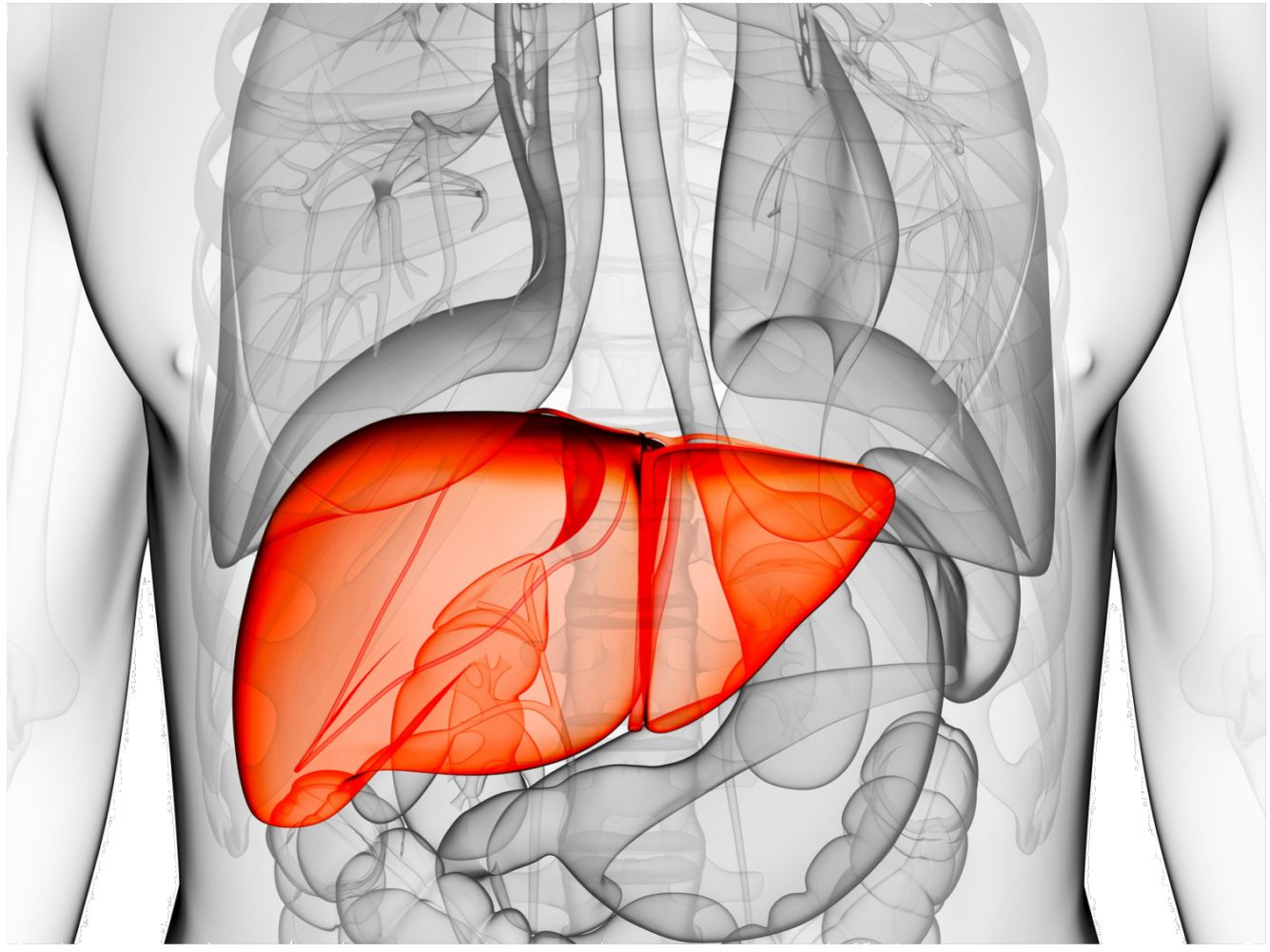

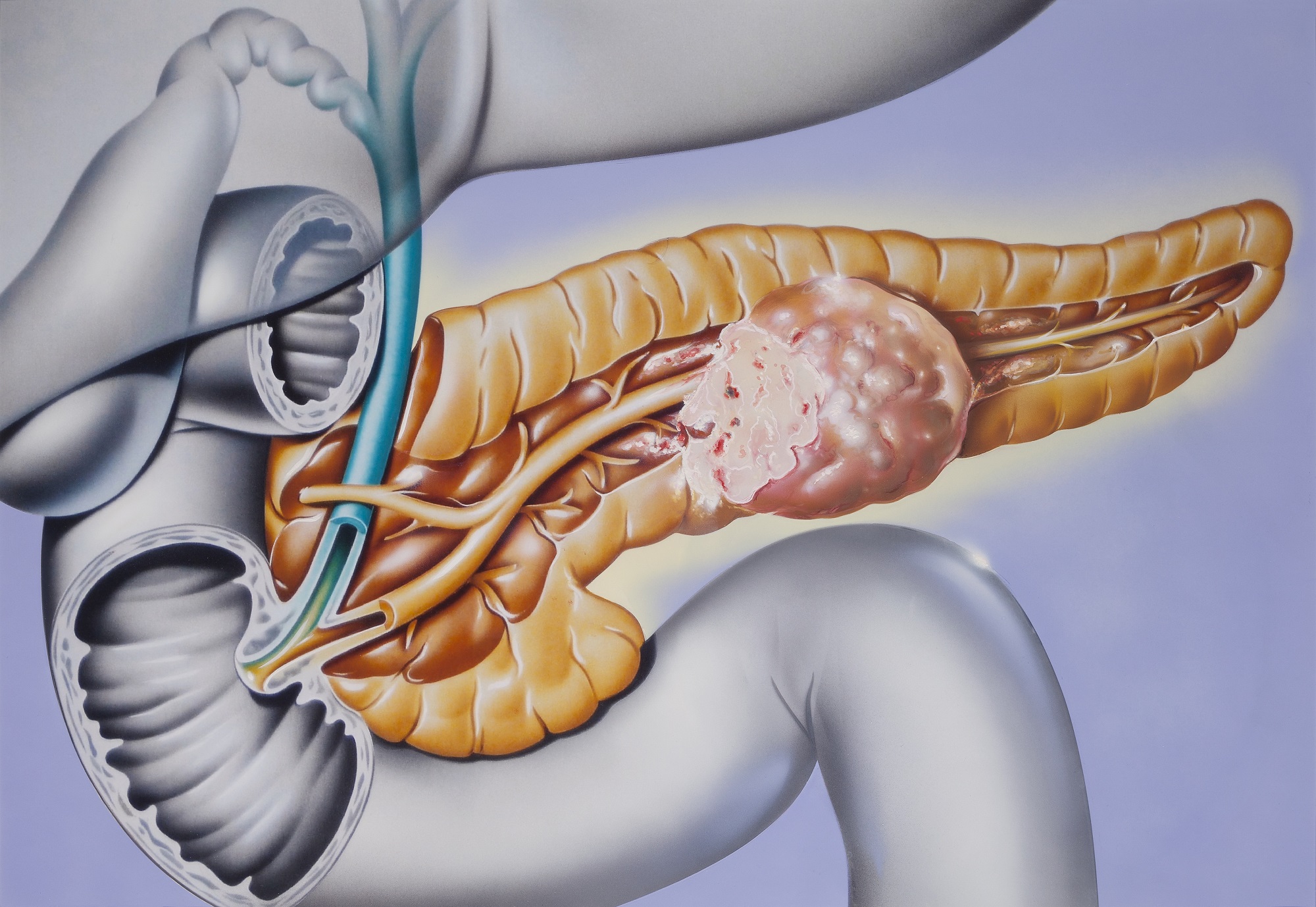

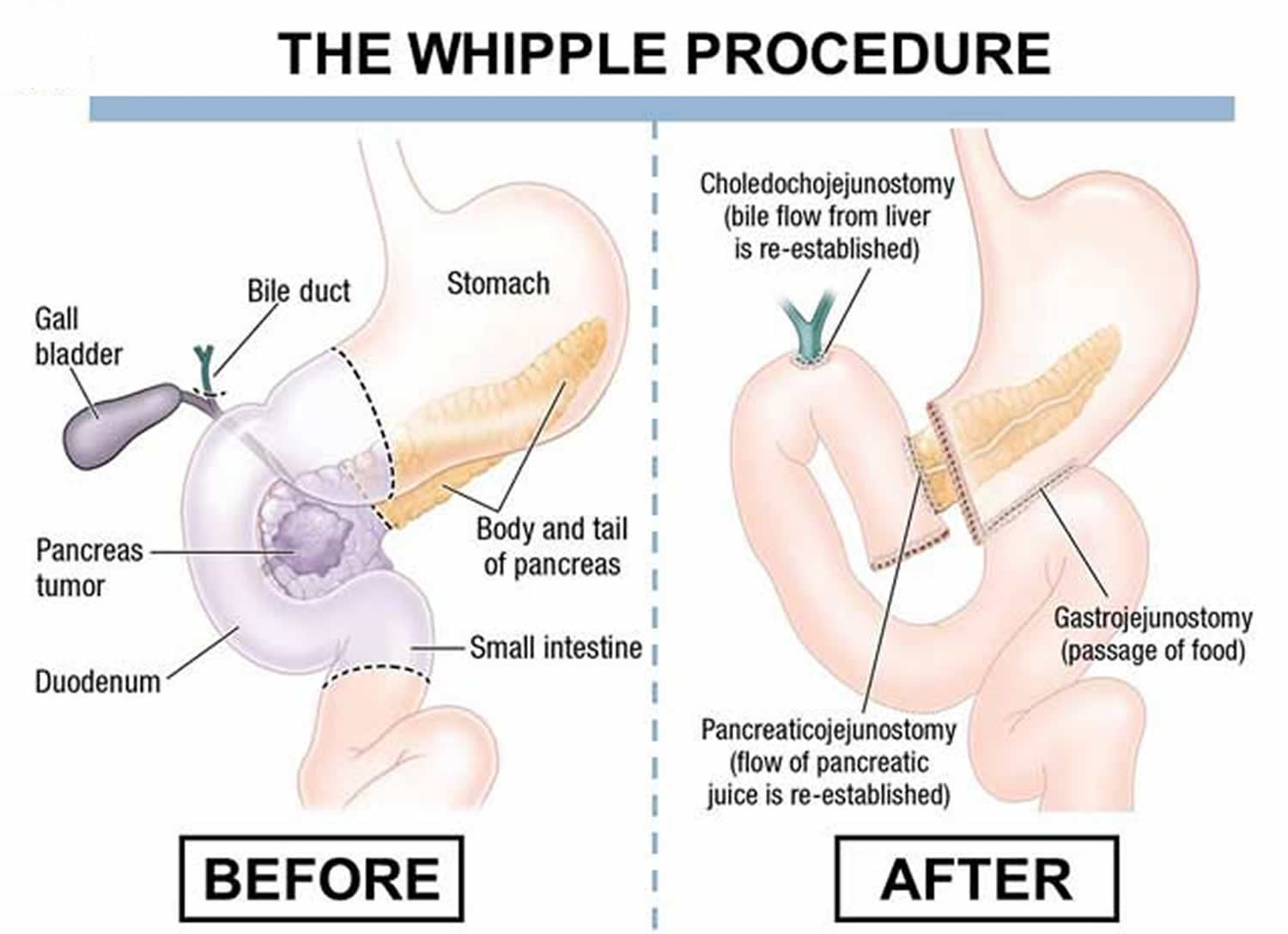

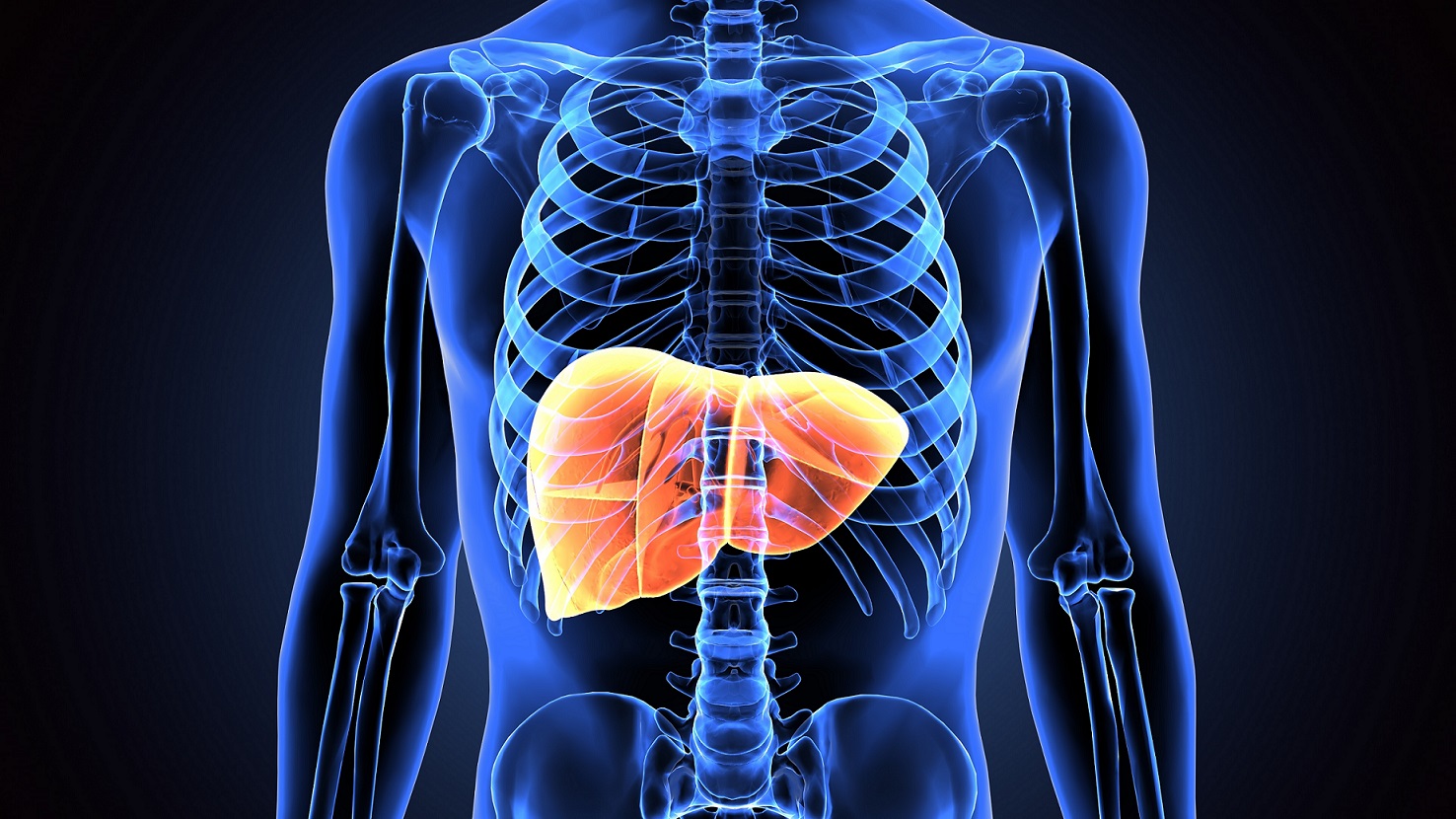

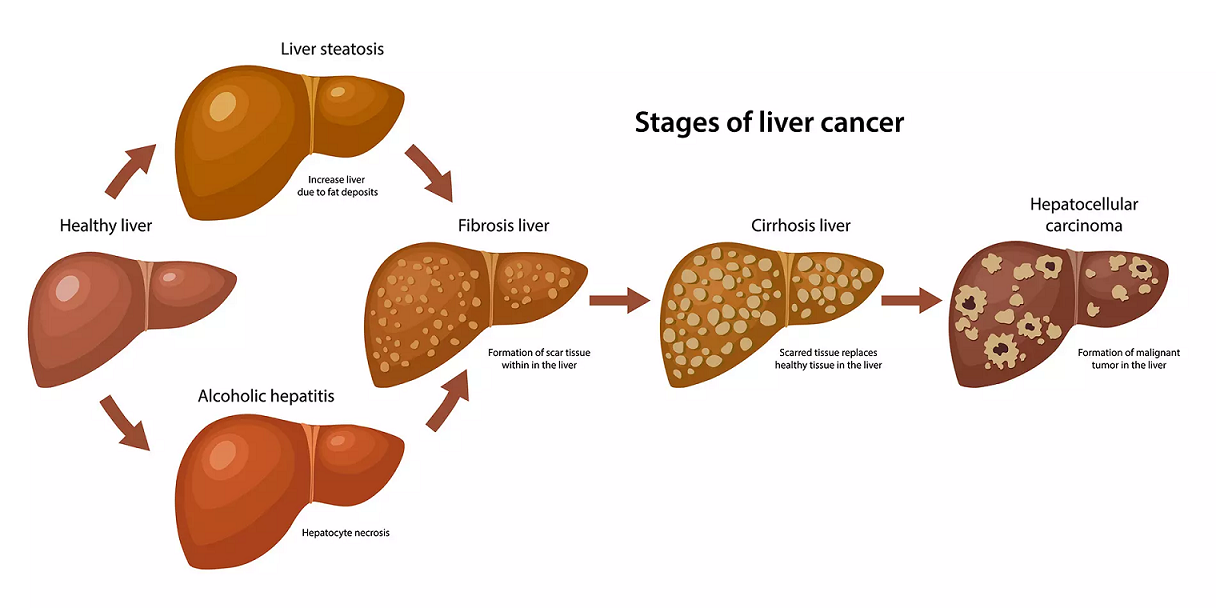

The risk of colorectal cancer recurrence can often be determined by the stage of the cancer. Stage I cancers have the lowest risk of cancer recurrence while stage II and III cancers have a higher risk of recurrence. Stage II cancers are those that do not have any lymph nodes involved, but the tumors grew deeper through the wall of the colon or rectum or invaded into other organs that are removed at the time of surgery. Stage III cancers refer to those that have spread to the lymph nodes. Stage IV tumors have spread to organs distant from the colon or rectum such as the liver, lungs or brain (see figure below). Due to the individual differences in Stage IV tumors, patients follow a more individualized follow-up routine.

HOW DO COLON AND RECTAL CANCERS RECUR?

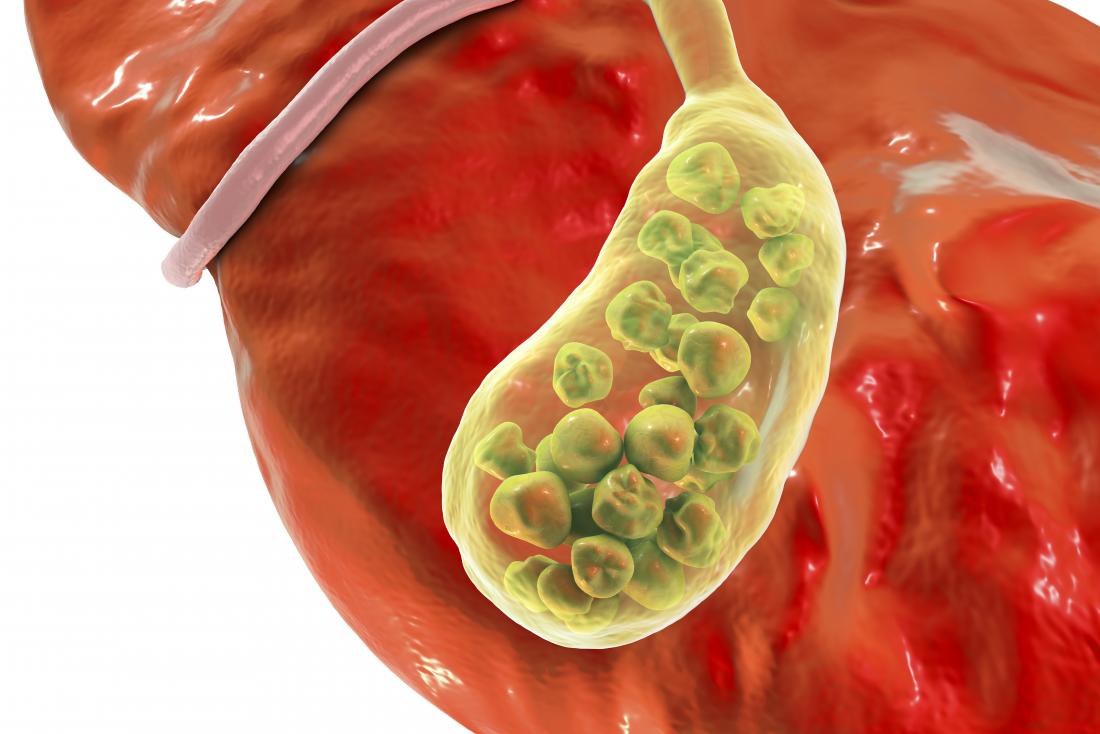

Two primary patterns of colorectal cancer recurrence are local and distant. Local recurrence refers to tumors recurring in the same area as the original tumor. Distant recurrence (metastatic disease) means cells from the original cancer have spread to distant organs, most often the liver or the lungs. Follow-up tests are aimed at detecting recurrent disease in these two main categories.

In addition, new colorectal cancers can develop at sites in the colon and rectum distinct from the place of the original tumor. This is not truly a recurrence, but rather a new cancer that develops sometime after the treatment of the original cancer.

FOLLOW-UP TESTING

Appropriate follow-up testing is key to the early detection and potentially successful management of cancer recurrence. These tests have been designed in order to attempt to pick up recurrences before the development of symptoms, so that intervention can be as successful as possible. The broad categories of follow-up testing include routine medical history and physical exam, blood tests such as serum carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), colonoscopy, and radiologic imaging.

MEDICAL HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

A medical history and physical exam are the most basic components of post-operative follow-up. While important, it is often the least effective way to detect early recurrences, because the vast majority of these do not have any signs or symptoms. These exams are most often performed by the cancer patient’s primary care physician or cancer specialist. A careful medical history may elicit new changes in bowel habits or the presence of new bleeding, or possibly unexplained weight loss. Any of these signs or symptoms should prompt a thorough workup. Pertinent physical examination findings may include the presence of rectal bleeding or a palpable mass. Abnormal lymph node enlargement may be felt in the groin lymph nodes, or more rarely masses may be felt during abdominal or rectal exam.

Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) is a protein that is made by some cancer cells, including colorectal cancer cells, and is secreted into the bloodstream.

CEA blood levels should be checked around the time of surgery and approximately every 3 months after treatment for at least 2 years in patients who have Stage II or III colon or rectal cancer. After a 2-year follow-up the CEA blood level is checked at least every 6 months for an additional three years.

Elevated levels may prompt additional workup such as imaging, with a CT scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis or a PET scan. Imaging may reveal the source of the recurrence, but occasionally may yield other incidental findings that may warrant workups.

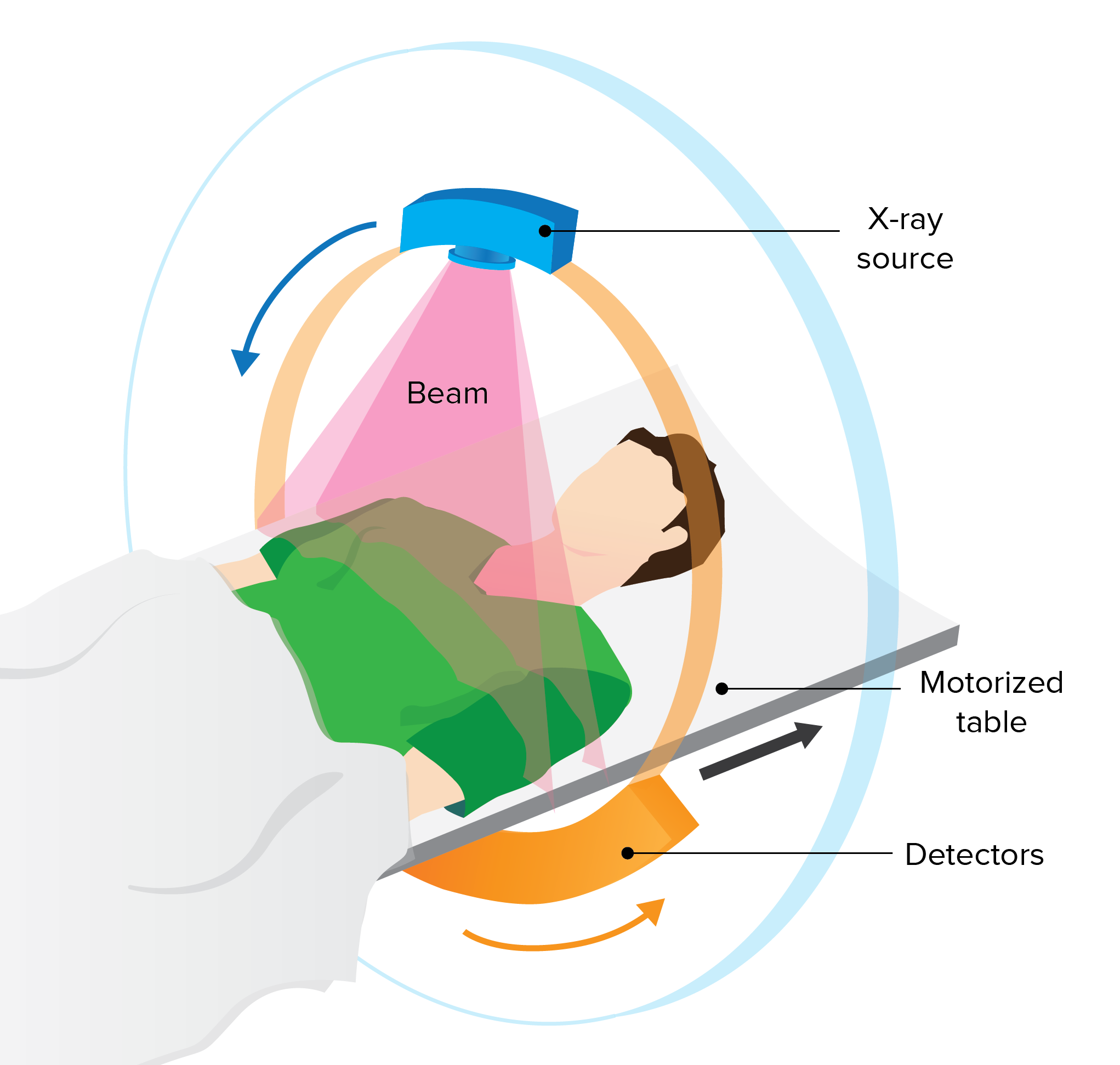

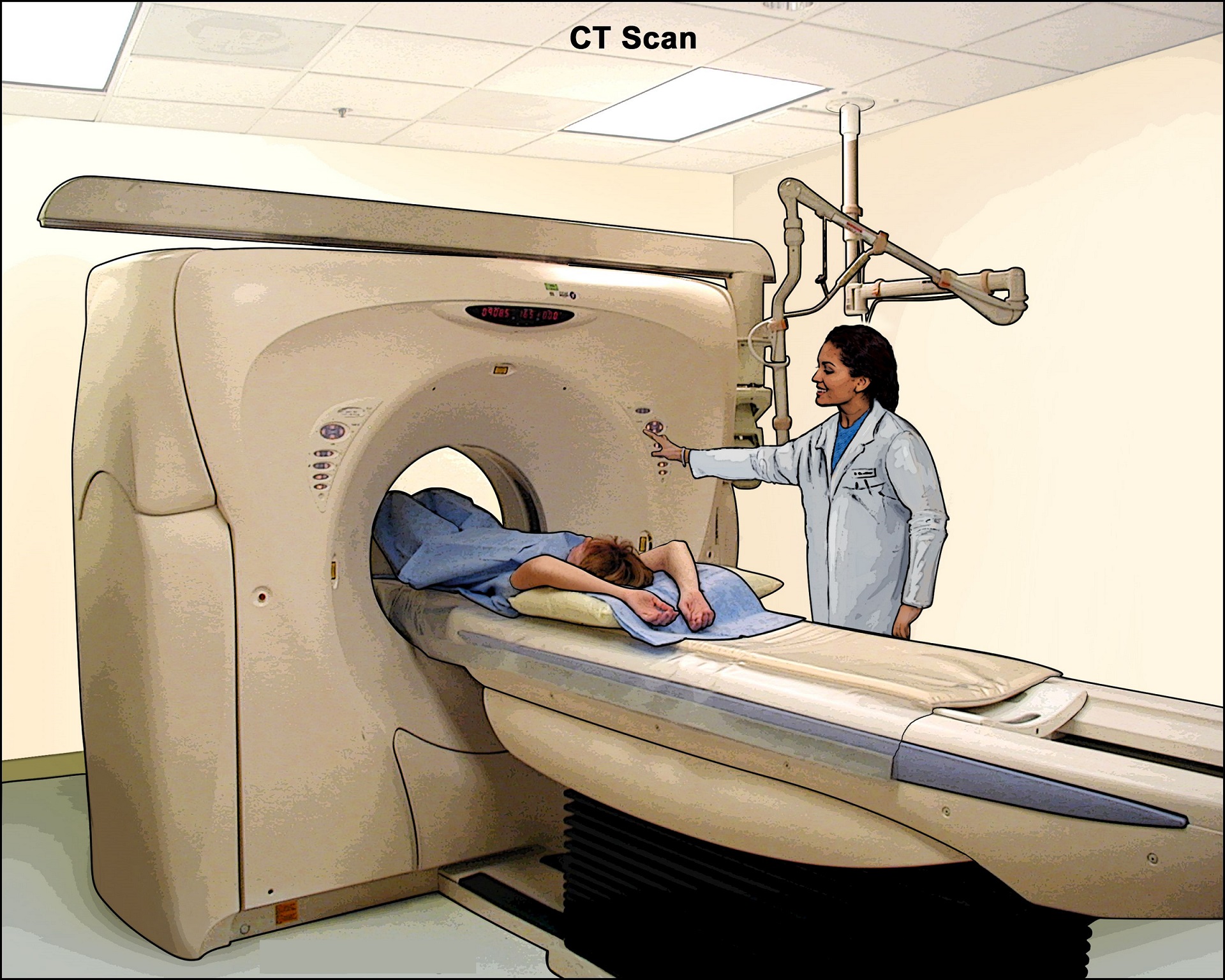

CT SCANNING

A computed tomography (CT) scan is a very sensitive X-ray test that allows physicians to see “inside” the body to identify new or recurrent tumors. Most patients who have had stage II or III colon or rectal cancer undergo yearly CT scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis.

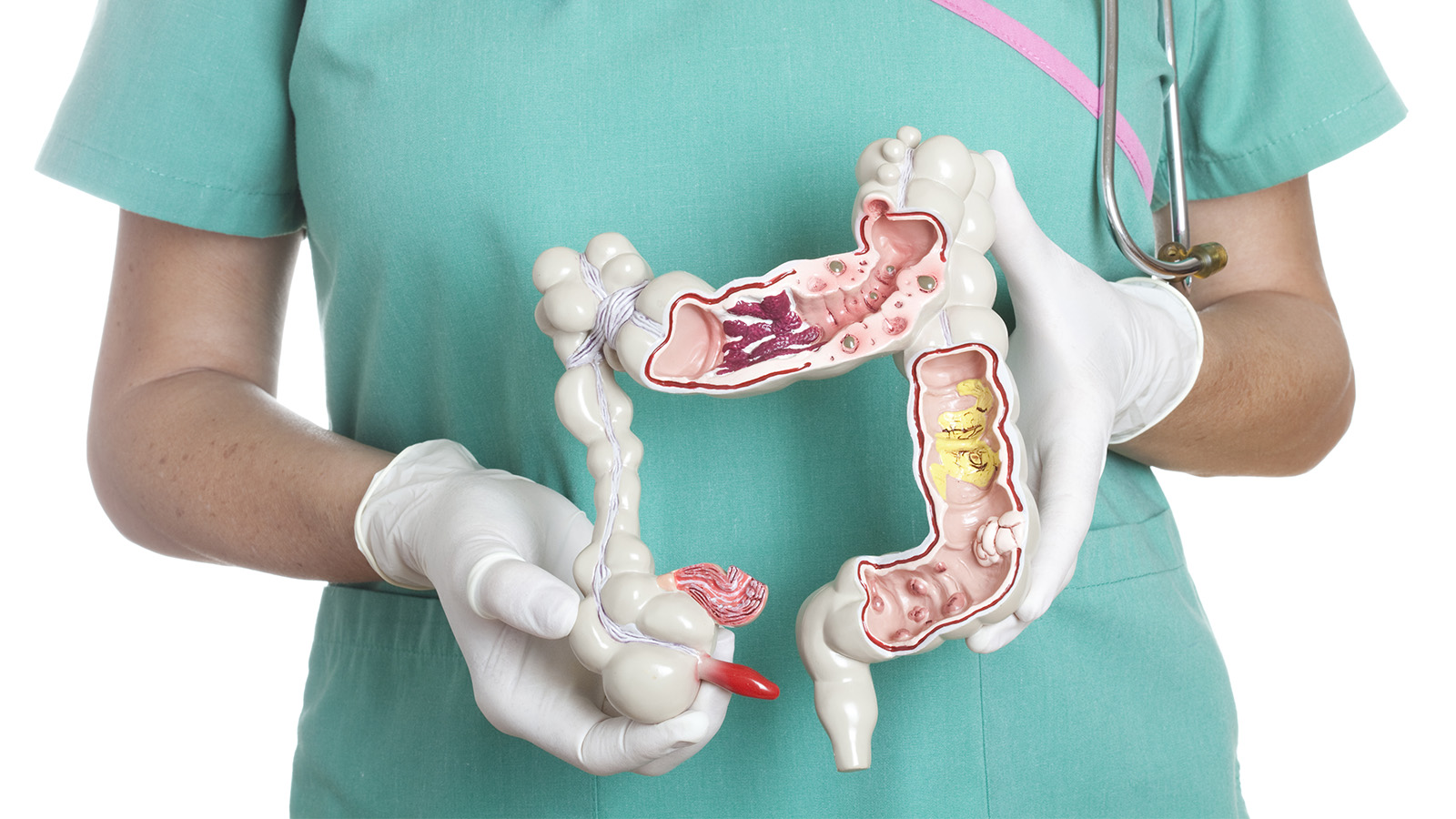

COLONOSCOPY, SIGMOIDOSCOPY, AND PROCTOSIGMOIDOSCOPY

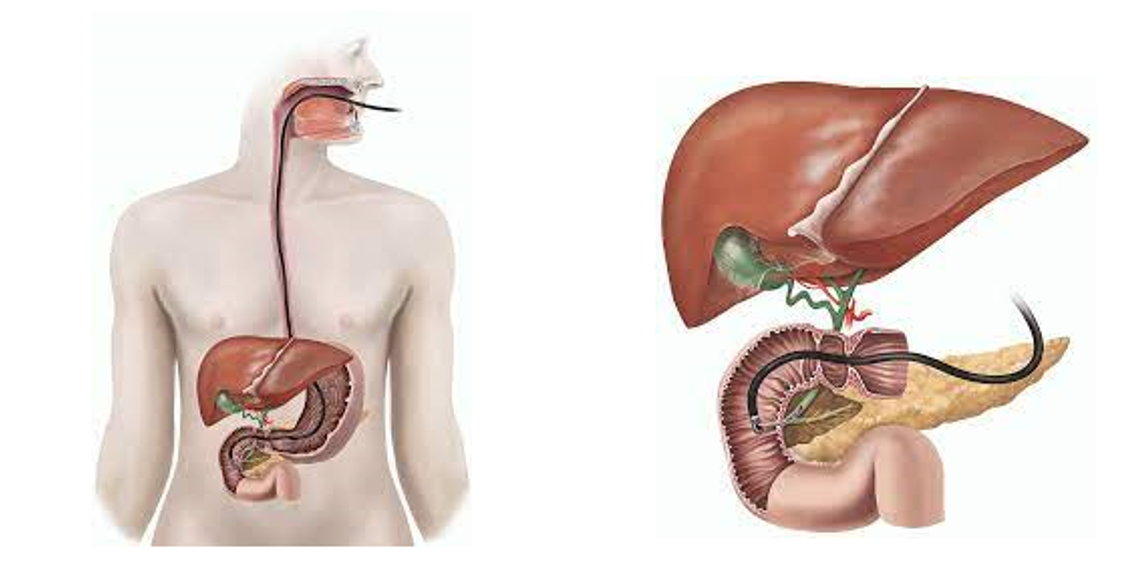

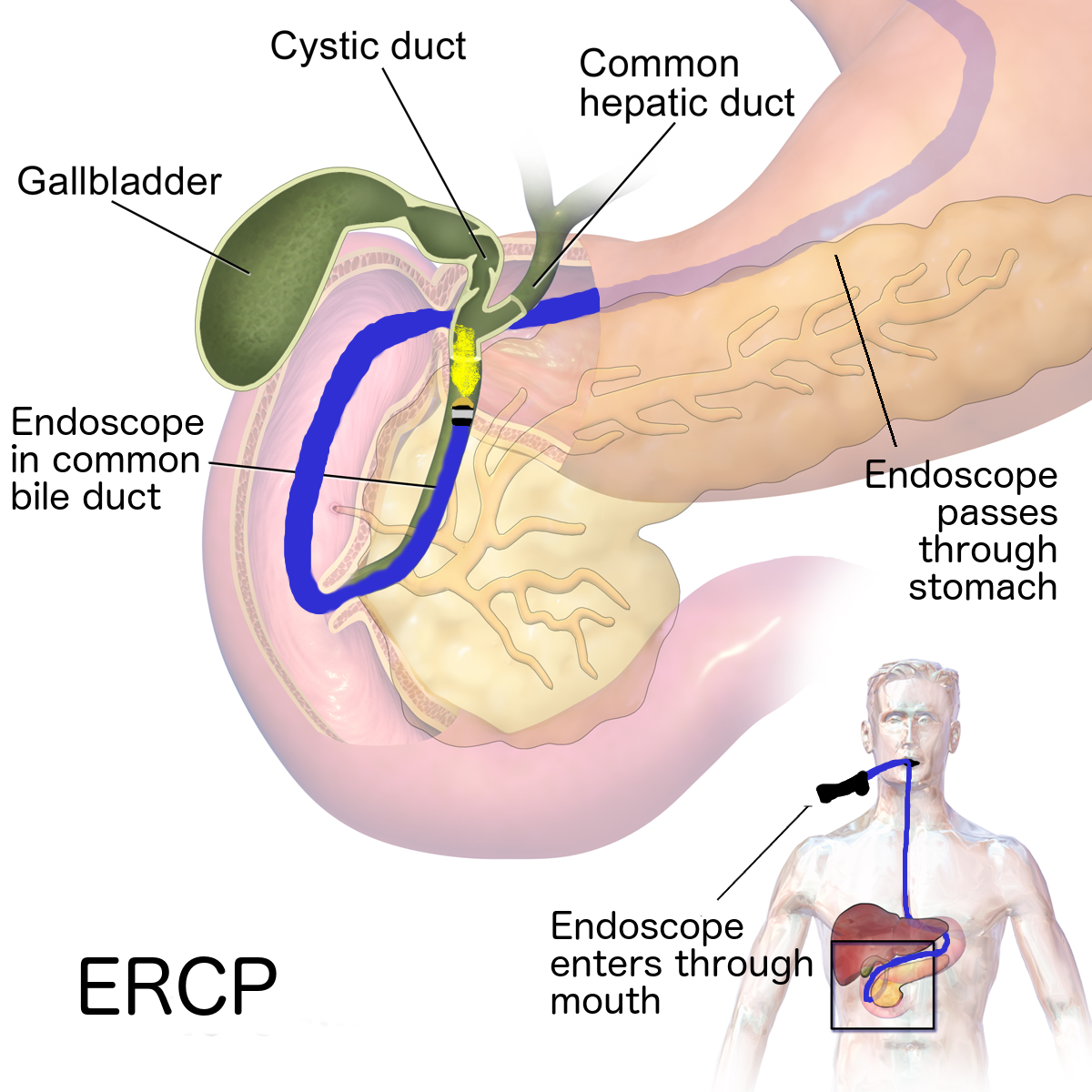

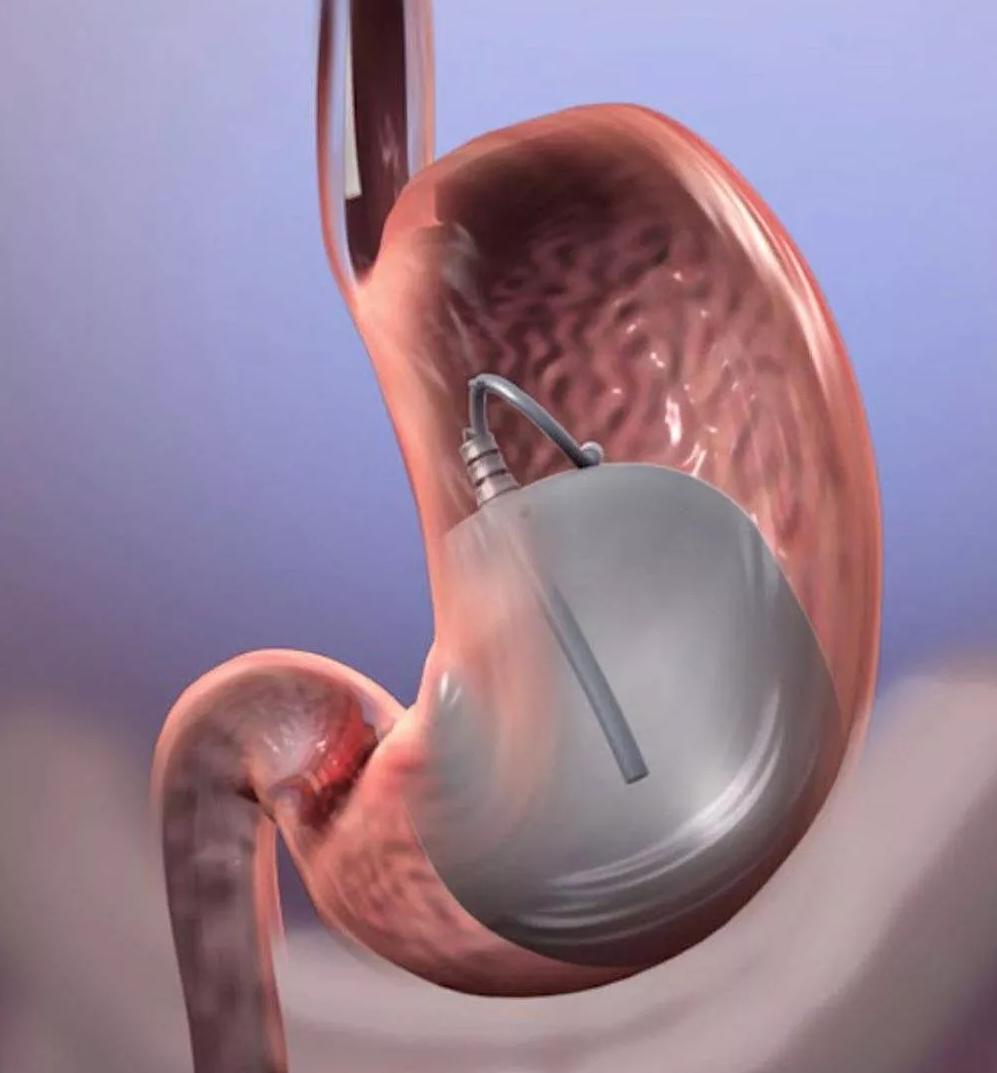

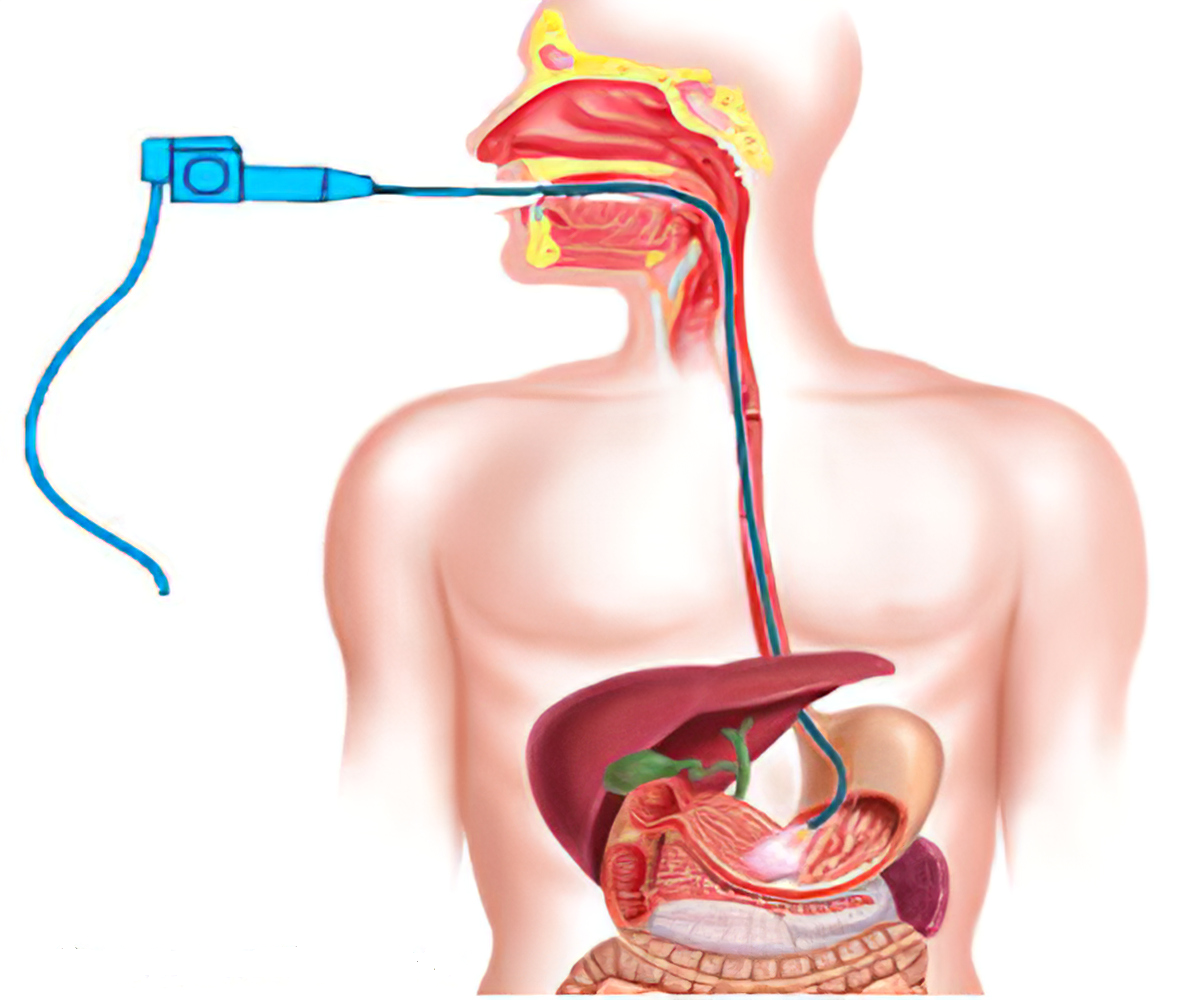

Colonoscopy and sigmoidoscopy are tests that allow the doctor to examine the entire colon or lower third of the colon, respectively. Flexible lighted cameras are inserted through the anus or through a colostomy to allow the physician to see the inside the bowel, to take pictures and biopsies, and to remove polyps. This procedure is usually performed as an outpatient at a surgery or endoscopy center. Patients are usually required to undergo bowel-cleansing procedures for 1 or 2 days prior to the procedure, so that the lining of the colon and rectum is clean and the entire area can be seen clearly.

Proctosigmoidoscopy can be performed with either a flexible or rigid (straight) scope. In this procedure, the scope is only advanced as far as the lowest portion of the colon. It is used in cases when the area to be examined is only the lower portion of the gastrointestinal tract.

Colonoscopy and flexible proctosigmoidoscopy are very safe procedures and rarely have serious complications. The two major risks associated with these procedures are significant bleeding and perforation of the colon. While they are of concern, in reality, they are rare, occurring in less than 1 or 2 of every 1,000 colonoscopies.

In some patients, genetic syndromes may cause their colorectal cancer. In these unique circumstances, screening or surveillance guidelines may be much more aggressive. Decisions regarding frequency of colonoscopy should be made in close consultation with your doctor and may involve follow-up with a genetics counselor.

OTHER TESTS

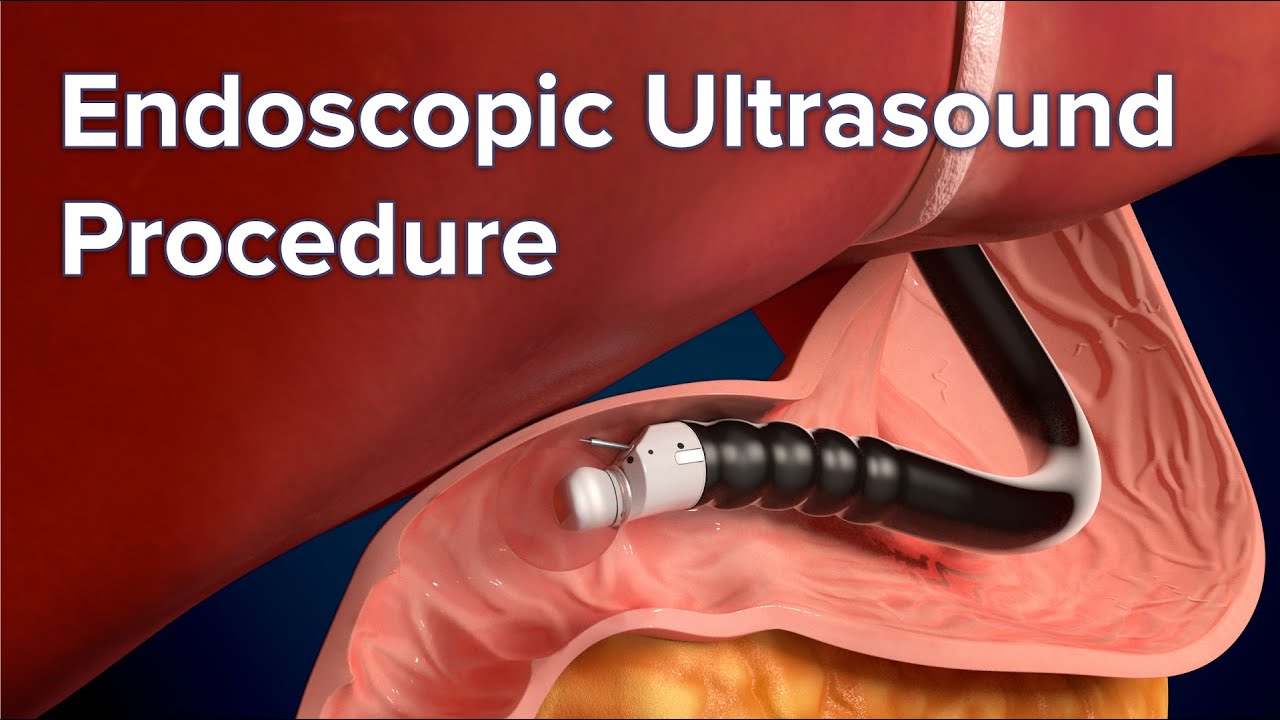

Rectal ultrasound is a test sometimes used to determine the depth of cancer invasion into the rectal wall for patients with rectal cancer. It is usually administered in the office or a procedure center. It may be performed by a radiologist, colorectal surgeon, or gastroenterologist. After a cleansing enema, the exam is usually performed with a rigid ultrasound probe or in conjunction with a flexible sigmoidoscopy.

Positron emission tomography (PET) scanning is a radiology test sometimes used to assess the potential for tumors to spread. For this test, a special, radioactively labeled form of glucose (sugar) is injected prior to scanning, and similar to a CT scan, the patient is placed in the PET scanner. Tumors and metastases will take up the glucose faster than other tissues, and appear as bright spots on a PET scan. This test is minimally invasive and very safe. The amount of radiation from the injected glucose is essentially harmless, and the test does not usually involve injection of any other dyes. Patients who are pregnant or plan to have children should discuss fertility issues with their physician prior to radiation exposure.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is another radiology test used to generate an image of a patient’s internal anatomy. Instead of using radiation, as a CT scan or X-ray does, images are based on the generation of a strong magnetic field. The images obtained in this manner can provide very specific anatomic detail, which can complement the information obtained through CT scans. MRI is usually a safe test, but it can be disconcerting for some patients, especially those with claustrophobia, because it involves being placed in a relatively narrow tunnel-like machine, often for 20 to 30 minutes. Patients are able to speak and interact with the technicians administering the test, but need to be able to keep very still. Patients with certain metal implants such as pacemakers may not be able to undergo MRI.

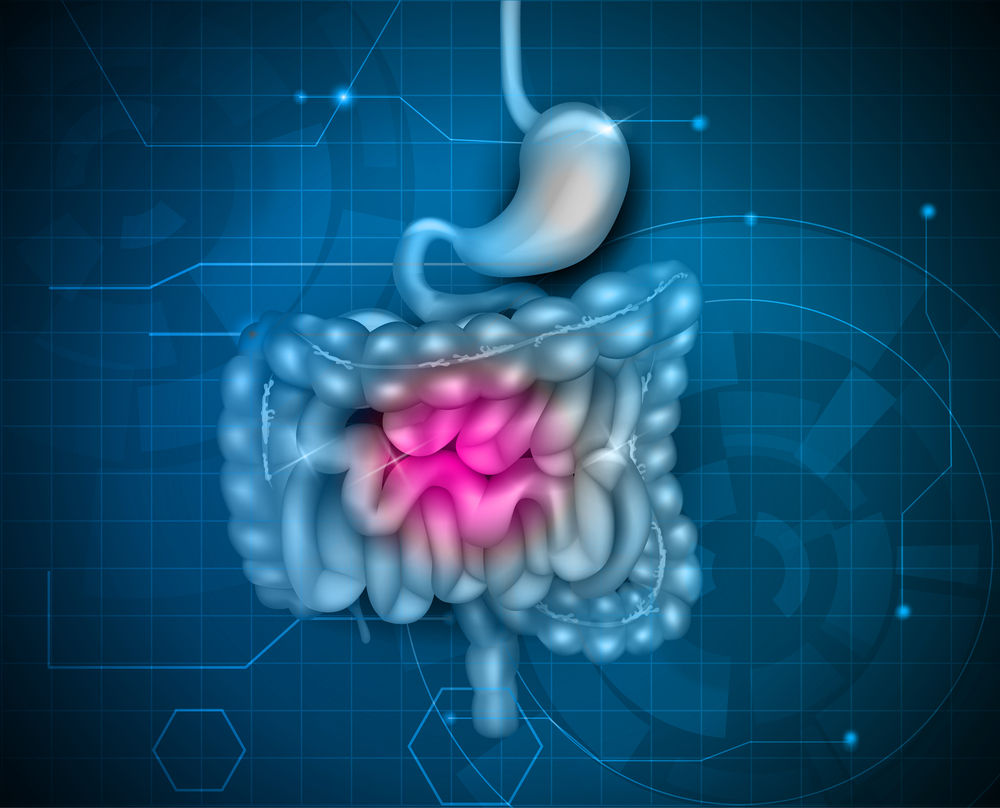

LOCAL RECURRENCE

Local recurrence is defined as colorectal cancer regrowing at the site of the original cancer. Since the original tumor was removed, along with the section of colon or rectum in which it arose, true local recurrence in the inner lining of the bowel may occur at the site of reconnection of the two pieces of intestine. These tumors may be visible inside the colon walls on colonoscopy as growths at or close to the reconnection site. They may grow into the inner lining of the bowel and cause symptoms related to bleeding or narrowing of the connection site.

If the narrowing is significant, patients may develop changes in bowel habits (less frequent bowel movements, narrow stools, difficulty pushing out the stool) or obstructive symptoms (absent bowel movements, abdominal pain, increase in size of abdomen, vomiting). Any changes in bowel habits in a patient with a previous colon or rectal resection should be reported to their physician, and likely will need to be evaluated with a colonoscopy. With early recurrences, the tumor may not cause any symptoms at all and may only be found during routine surveillance.

Local recurrences may also occur outside the bowel wall. These recurrences are often initially asymptomatic and not detectable by colonoscopy, since only the inside of the bowel is visible on a colonoscopy. These recurrences are usually detected either by surveillance X-rays (e.g., CT scan) or are signaled by an increase in the CEA level (see below). When these outside local recurrences grow into certain structures, they may cause secondary symptoms, such as pain, or symptoms from other organ systems that they invade. Recurrences outside of the colon causing symptoms are often associated with a poor outcome.

DISTANT RECURRENCE

Distant recurrences occur in patients with delayed metastatic disease (spread to other organs not in direct contact with the initial tumor, most often through lymph nodes or the bloodstream). The most common sites for distant recurrence of colon and rectal cancer are the liver and the lungs. These recurrences often do not have any symptoms and are only found during routine follow up X-rays or abnormal CEA testing which prompts imaging to look for the possible source.

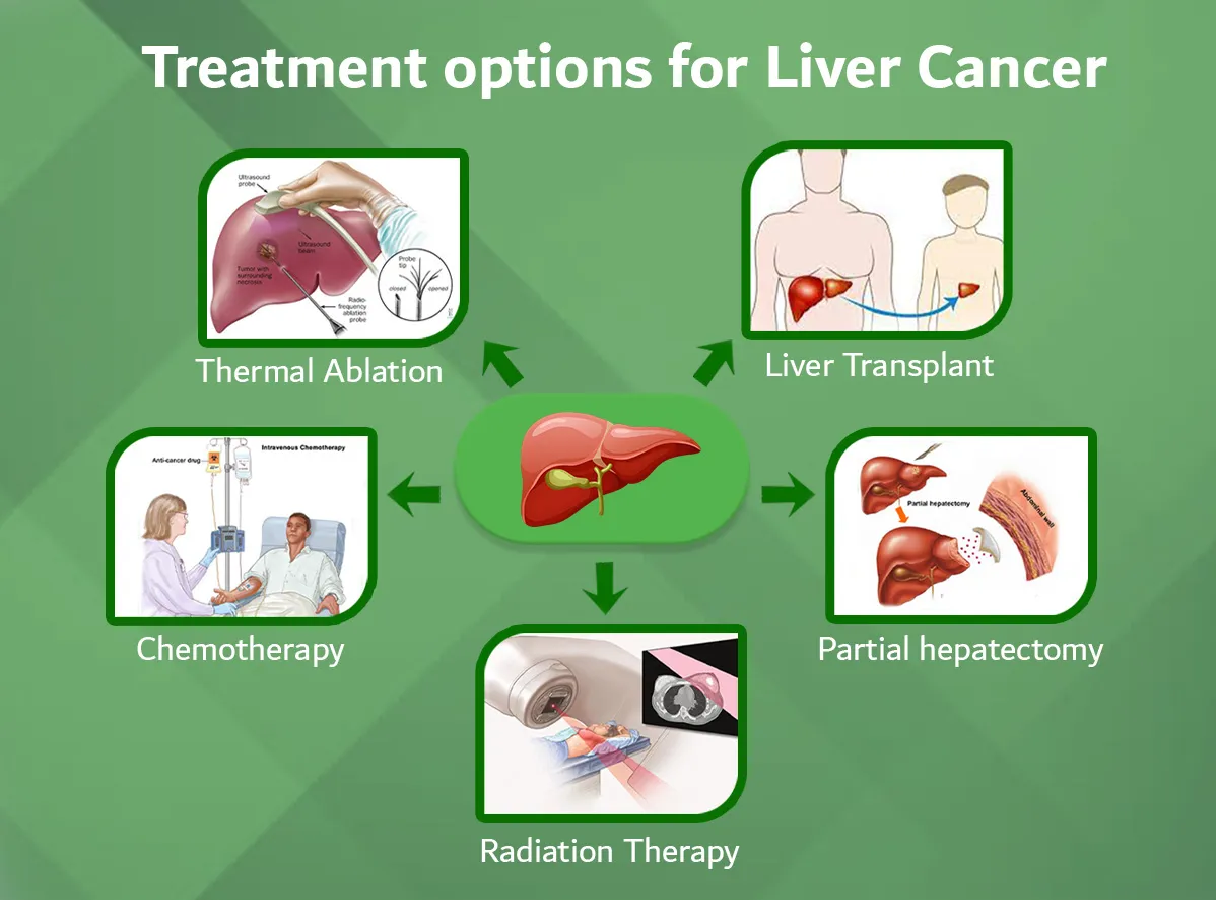

WHAT HAPPENS IF RECURRENCE IS FOUND?

If a recurrence is found during regular follow-up, your cancer specialist and your colorectal surgeon will work together to determine how extensive it is. Most likely, imaging tests, such as a CT scan or PET scan will be performed to determine whether there has been additional distant spread. If the recurrence is distant from the original tumor, or in more than one area, this is usually treated initially with chemotherapy. If the recurrence is local, it may be possible to treat it with another surgery. If your original cancer was in the colon (not the rectum), it is more likely that this local recurrence will be able to be removed.

If the local recurrence is in the rectum, this can pose specific problems when adjacent structures are involved. Attempts at surgery for cure may involve the need for removal of a portion of the sacrum (tailbone), parts of the urinary system, and vagina. In order to determine if other organs are involved, usually an MRI of the pelvis is obtained. In addition, if the patient hasn’t already received radiation before their rectal cancer surgery, it is almost always indicated in the treatment of recurrent rectal cancer.