Achalasia

OVERVIEW | CAUSES | RISK FACTORS | SYMPTOMS | COMPLICATION | Diagnosis | TREATMENT | PREVENTION | REFERENCES

Overview

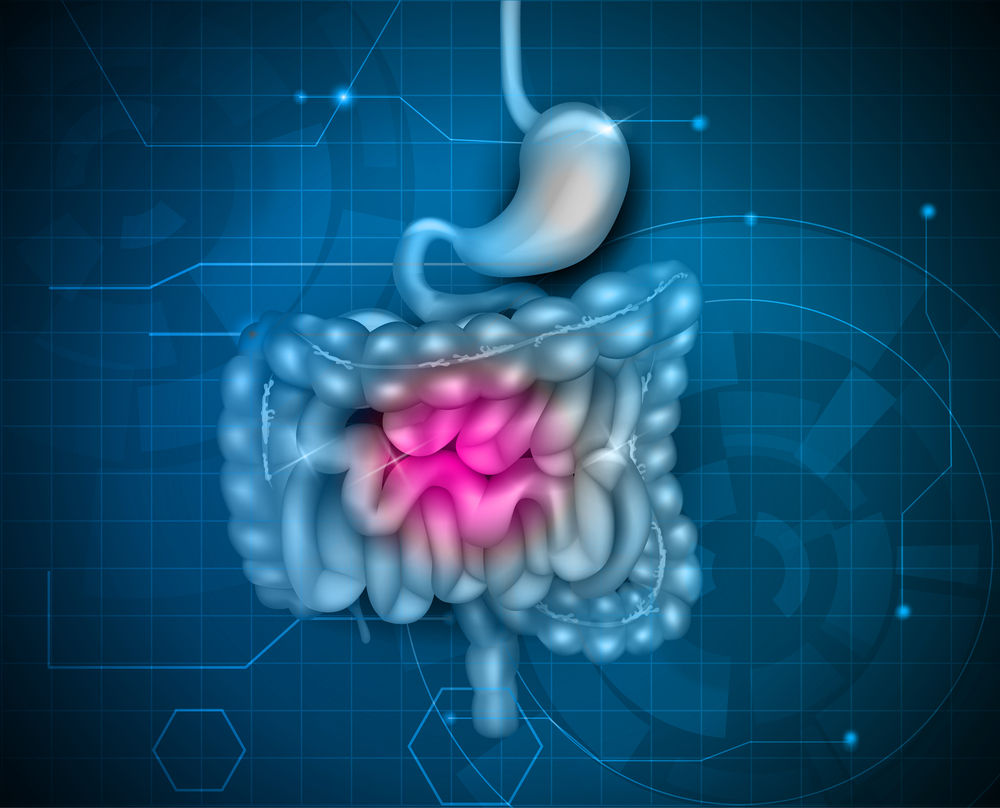

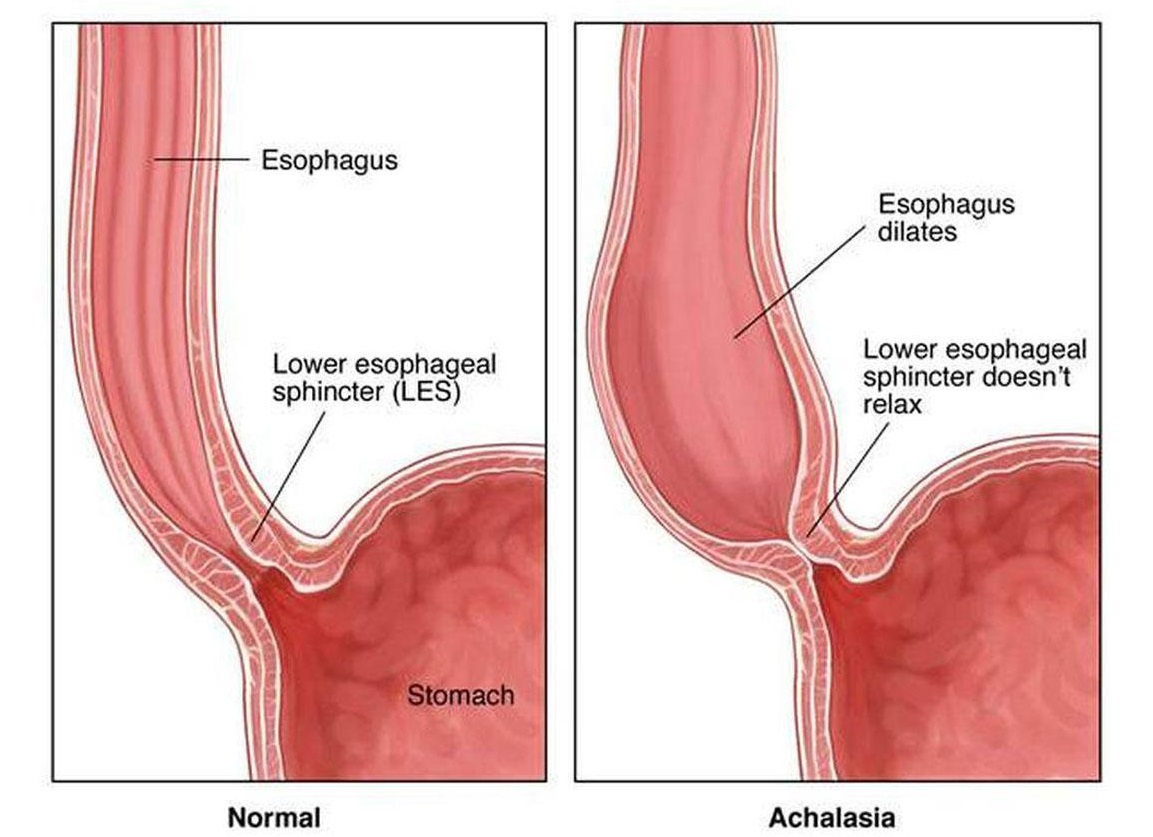

Achalasia is a rare disorder that makes it difficult for food and liquid to pass from the swallowing tube connecting your mouth and stomach (esophagus) into your stomach.

Achalasia occurs when nerves in the esophagus get damaged. As a result, the esophagus becomes paralyzed and dilated over time and eventually loses the ability to squeeze food down into the stomach.

Food then collects in the esophagus, sometimes fermenting and washing back up into the mouth, which can taste bitter.

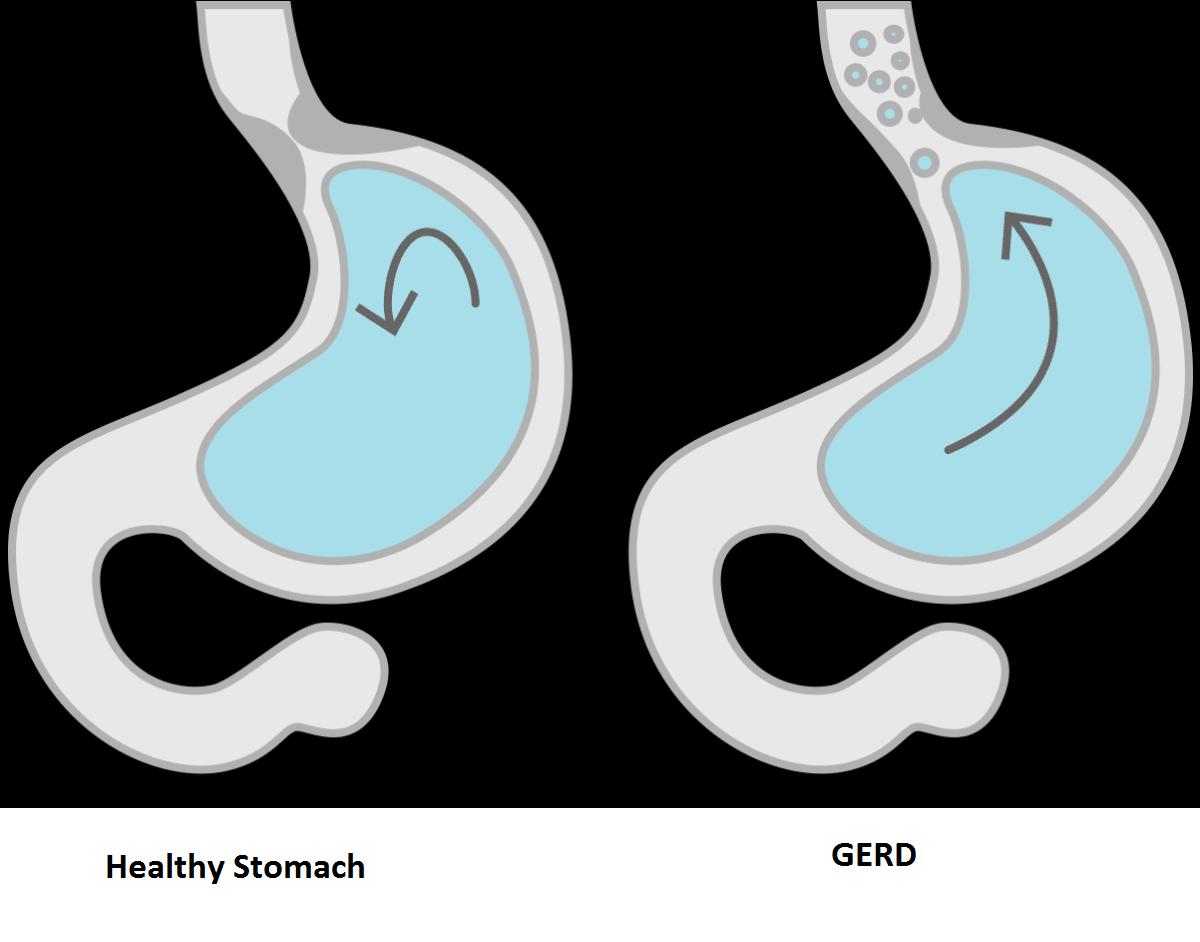

Some people mistake this for gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). However, in achalasia the food is coming from the esophagus, whereas in GERD the material comes from the stomach.

There's no cure for achalasia. Once the esophagus is paralyzed, the muscle cannot work properly again. But symptoms can usually be managed with endoscopy, minimally invasive therapy or surgery.

Causes

The cause of achalasia is unknown. Theories on causation invoke infection, heredity or an abnormality of the immune system that causes the body itself to damage the esophagus (autoimmune disease).

The esophagus contains both muscles and nerves. The nerves coordinate the relaxation and opening of the sphincters as well as the peristaltic waves in the body of the esophagus.

Achalasia has effects on both the muscles and nerves of the esophagus; however, the effects on the nerves are believed to be the most important. Early in achalasia, inflammation can be seen (when a medical professional examines esophageal tissue under the microscope) in the muscle of the lower esophagus, especially around the nerves.

As the disease progresses, the nerves begin to degenerate and ultimately disappear, particularly the nerves that cause the lower esophageal sphincter to relax.

Still later in the progression of the disease, muscle cells begin to degenerate, possibly because of the damage to the nerves.

The result of these changes is a lower sphincter that cannot relax and muscle in the lower esophageal body that cannot support peristaltic waves. With time, the body of the esophagus stretches and becomes enlarged (dilated).

Risk factors

Achalasia can occur at any age. But it happens most often between ages 30 and 60. Men and women are equally at risk.

Healthcare providers don’t know why achalasia happens. But risk factors may include:

- Genes you are born with

- A problem with your immune system that causes it to attack nerve cells in your esophagus

- Having herpes simplex virus or other viral infections

- Having Chagas disease. This is an infection caused by a parasite. The parasite is passed to people through the bite of an insect. Chagas disease is mainly found in poor rural areas of Mexico and Central and South America.

Symptoms

Achalasia symptoms generally appear gradually and worsen over time. Signs and symptoms may include:

- Inability to swallow (dysphagia), which may feel like food or drink is stuck in your throat

- Regurgitating food or saliva

- Heartburn

- Belching

- Chest pain that comes and goes

- Coughing at night

- Pneumonia (from aspiration of food into the lungs)

- Weight loss

- Vomiting

Complications

Treatment can help prevent long-term complications such as:

- Aspiration pneumonia. This is caused when food or liquids in your esophagus back up into your throat and you breathe them into your lungs.

- Esophageal perforation. This is a hole in the esophagus. It may happen if the walls of your esophagus become weak and bulge. It may also happen during treatment. Esophageal perforation may cause a life-threatening infection.

- Esophageal cancer. People with achalasia are at higher risk for this type of cancer.

Diagnosis

Achalasia can be overlooked or misdiagnosed because it has symptoms similar to other digestive disorders. To test for achalasia, your doctor is likely to recommend:

1. Esophageal manometry.

This test measures the rhythmic muscle contractions in your esophagus when you swallow, the coordination and force exerted by the esophagus muscles, and how well your lower esophageal sphincter relaxes or opens during a swallow. This test is the most helpful when determining which type of motility problem you might have.

2. X-rays of your upper digestive system (esophagram).

X-rays are taken after you drink a chalky liquid that coats and fills the inside lining of your digestive tract. The coating allows your doctor to see a silhouette of your esophagus, stomach and upper intestine. You may also be asked to swallow a barium pill that can help to show a blockage of the esophagus.

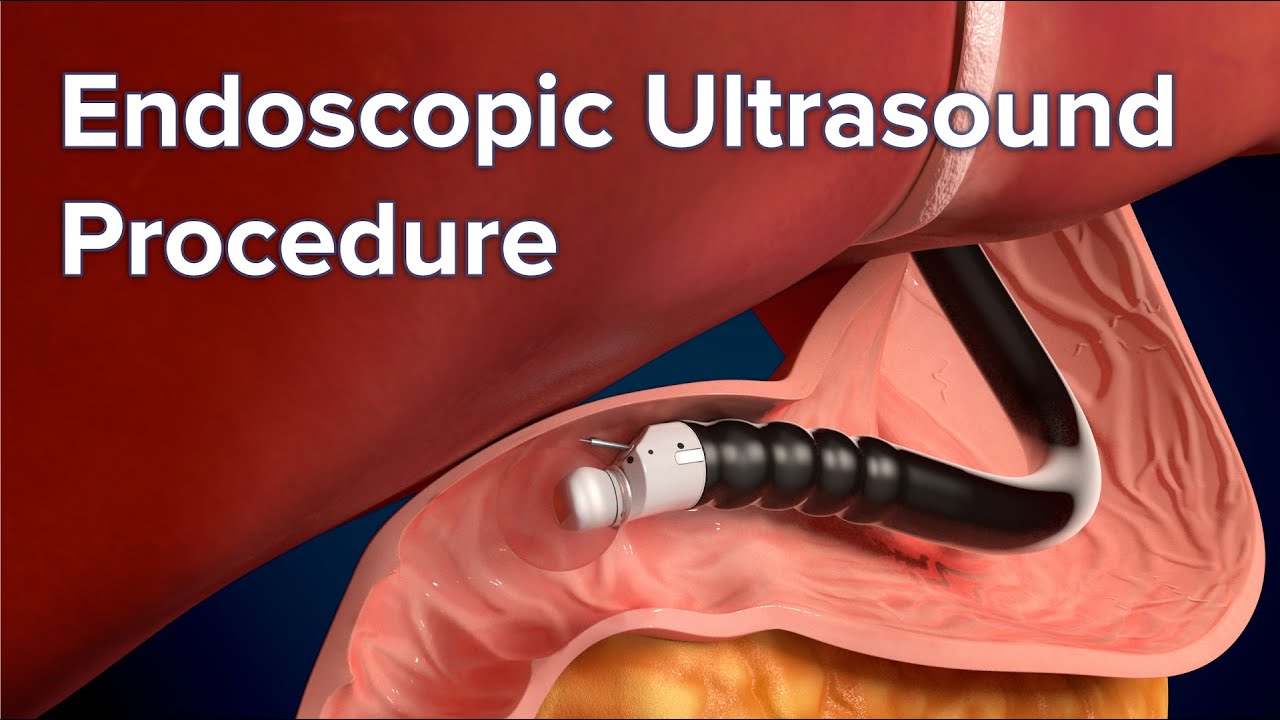

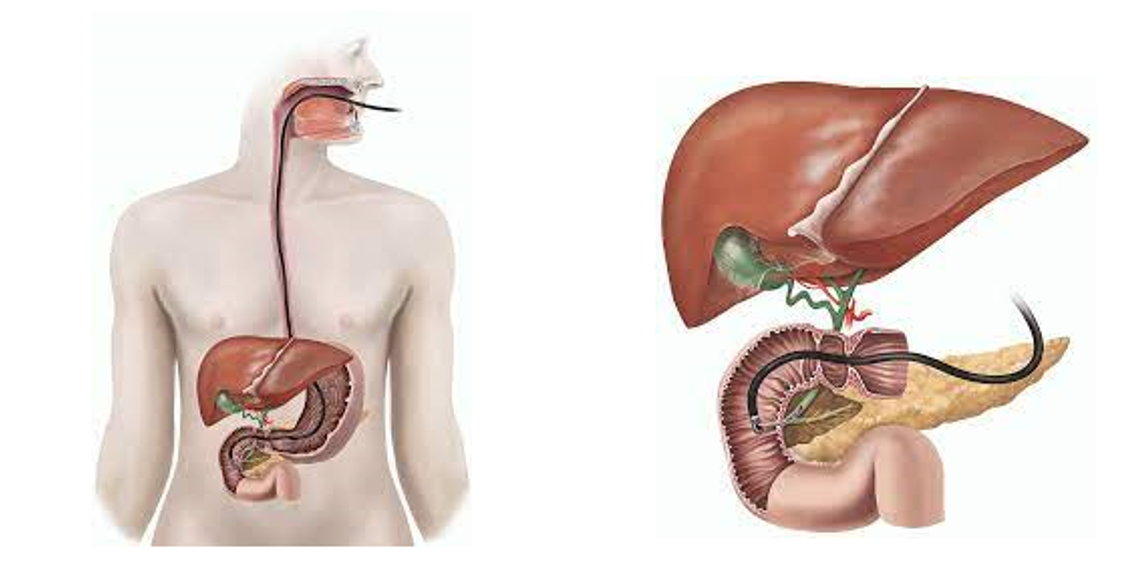

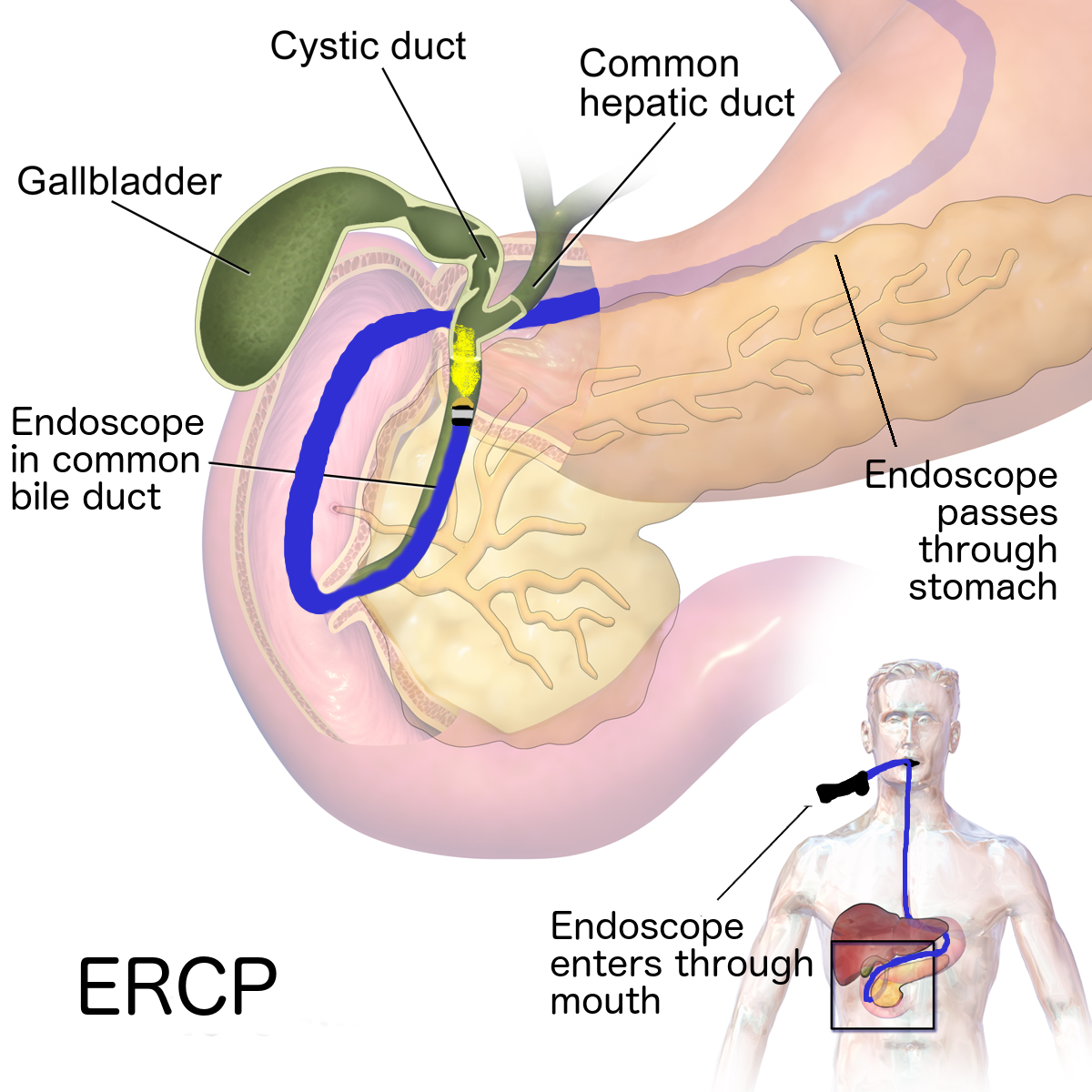

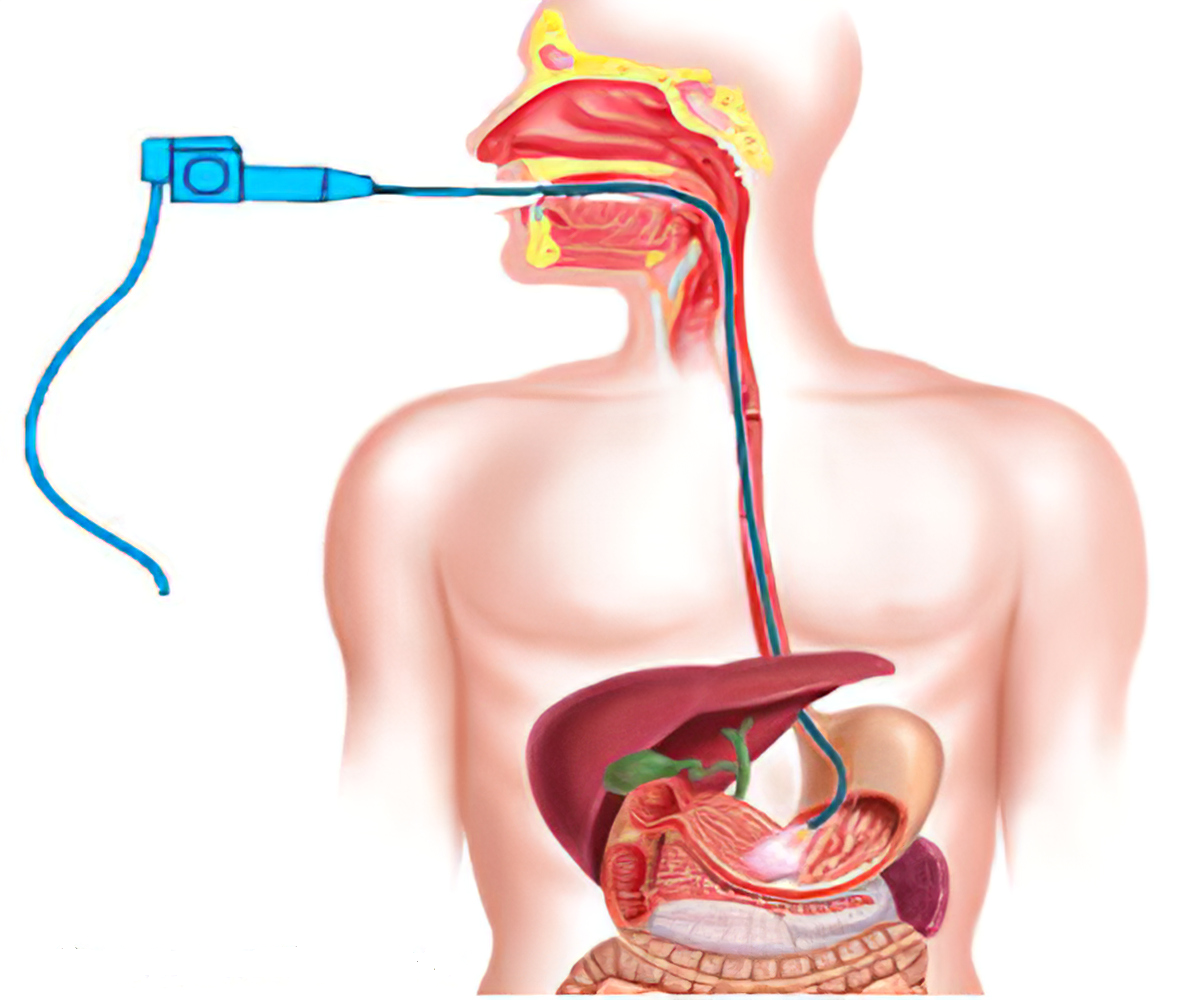

3. Upper endoscopy.

Your doctor inserts a thin, flexible tube equipped with a light and camera (endoscope) down your throat, to examine the inside of your esophagus and stomach. Endoscopy can be used to define a partial blockage of the esophagus if your symptoms or results of a barium study indicate that possibility. Endoscopy can also be used to collect a sample of tissue (biopsy) to be tested for complications of reflux such as Barrett's esophagus.

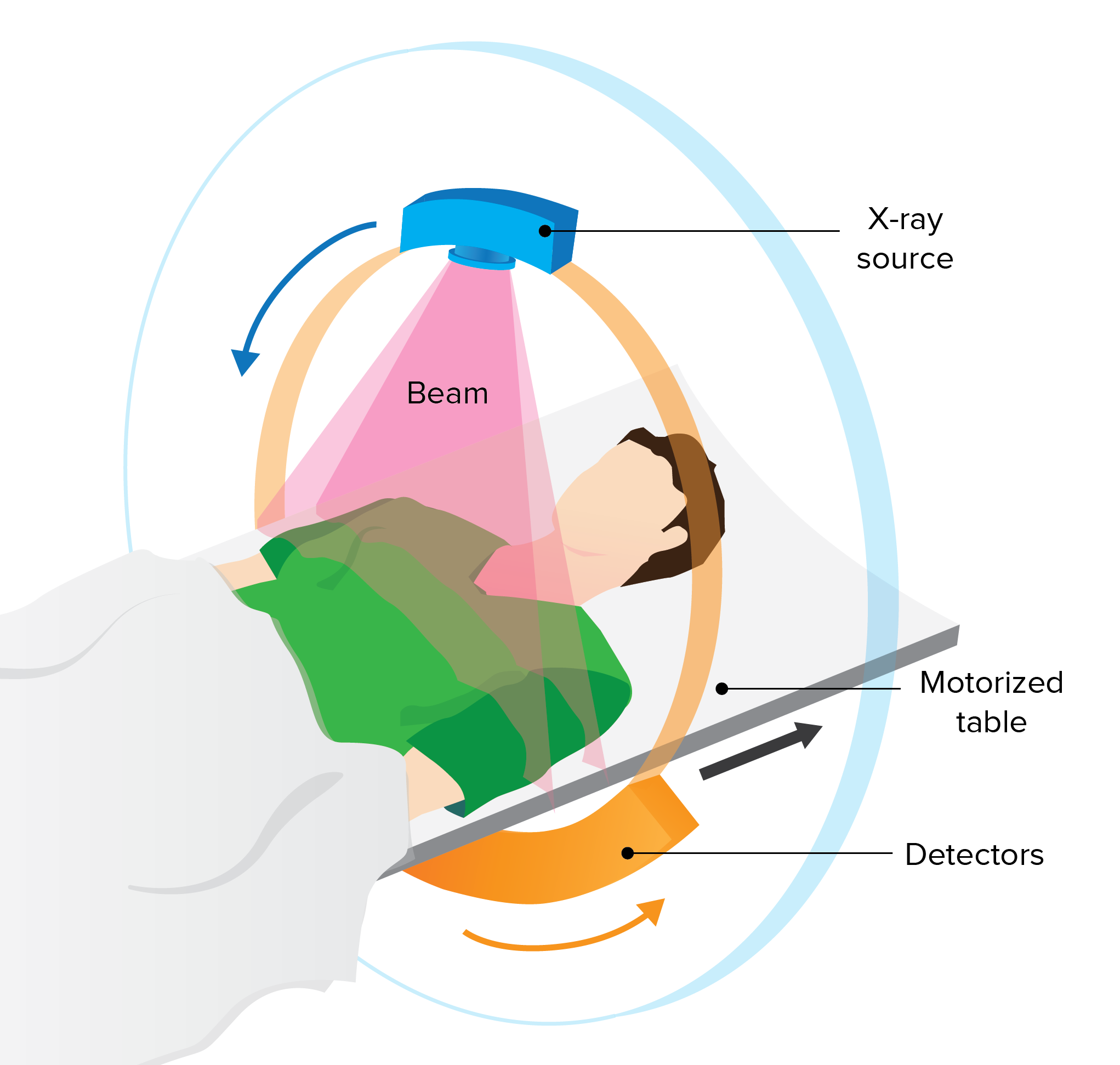

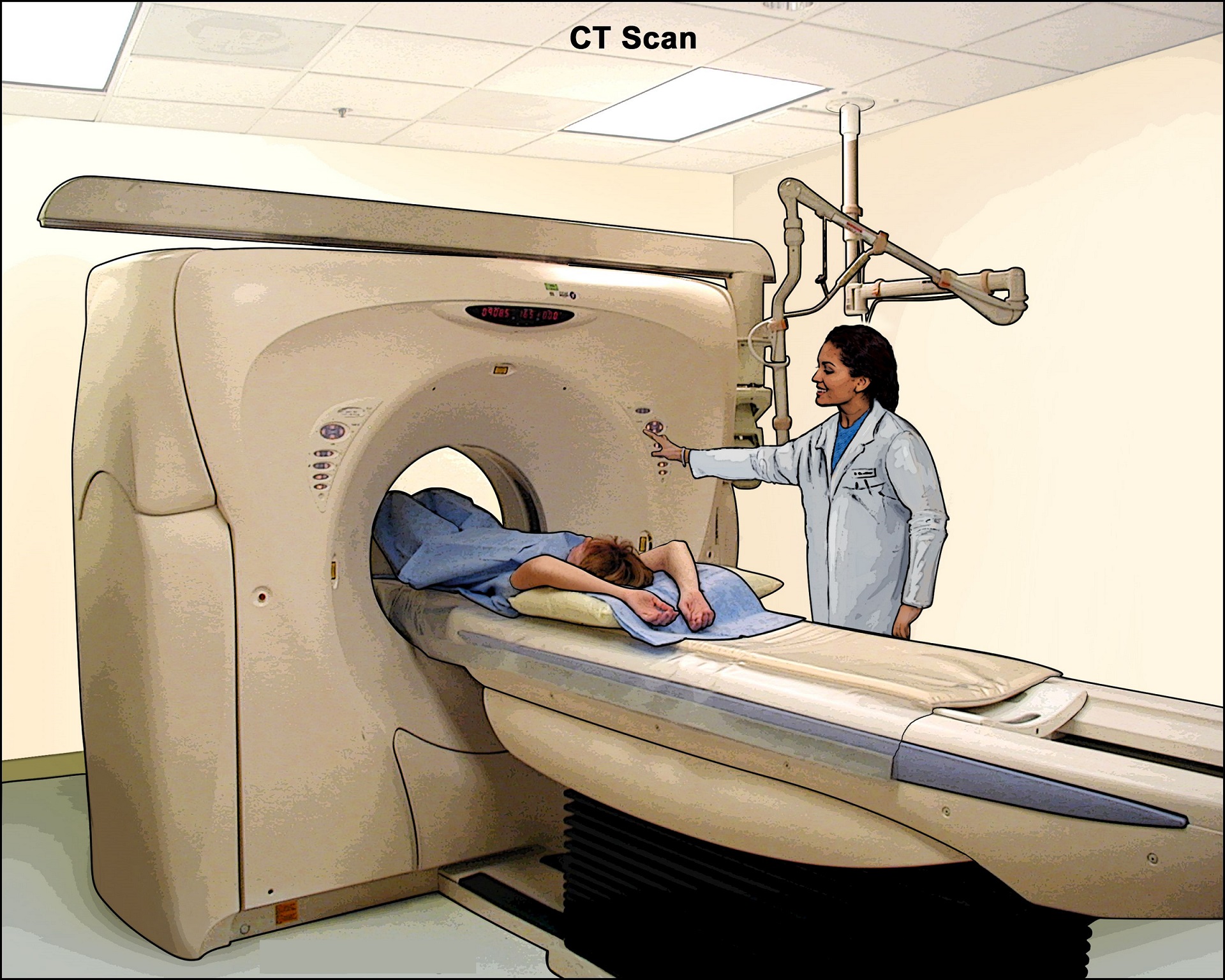

4. CT Scan:

Patients with uncomplicated achalasia demonstrate a dilated, thin-walled esophagus filled with fluid/food debris. Overall, CT has little role in directly assessing patients with achalasia, but is useful in assessing common complications. Careful assessment of the wall of the esophagus should be undertaken to identify any focal regions of thickening which may indicate malignancy. The lungs should be inspected for evidence of aspiration.

Treatment

Achalasia treatment focuses on relaxing or stretching open the lower esophageal sphincter so that food and liquid can move more easily through your digestive tract.

Specific treatment depends on your age, health condition and the severity of the achalasia.

Nonsurgical treatment

Nonsurgical options include:

- Medication. Your doctor might suggest muscle relaxants such as nitroglycerin (Nitrostat) or nifedipine (Procardia) before eating. These medications have limited treatment effects and severe side effects. Medications are generally considered only if you're not a candidate for pneumatic dilation or surgery, and Botox hasn't helped. This type of therapy is rarely indicated.

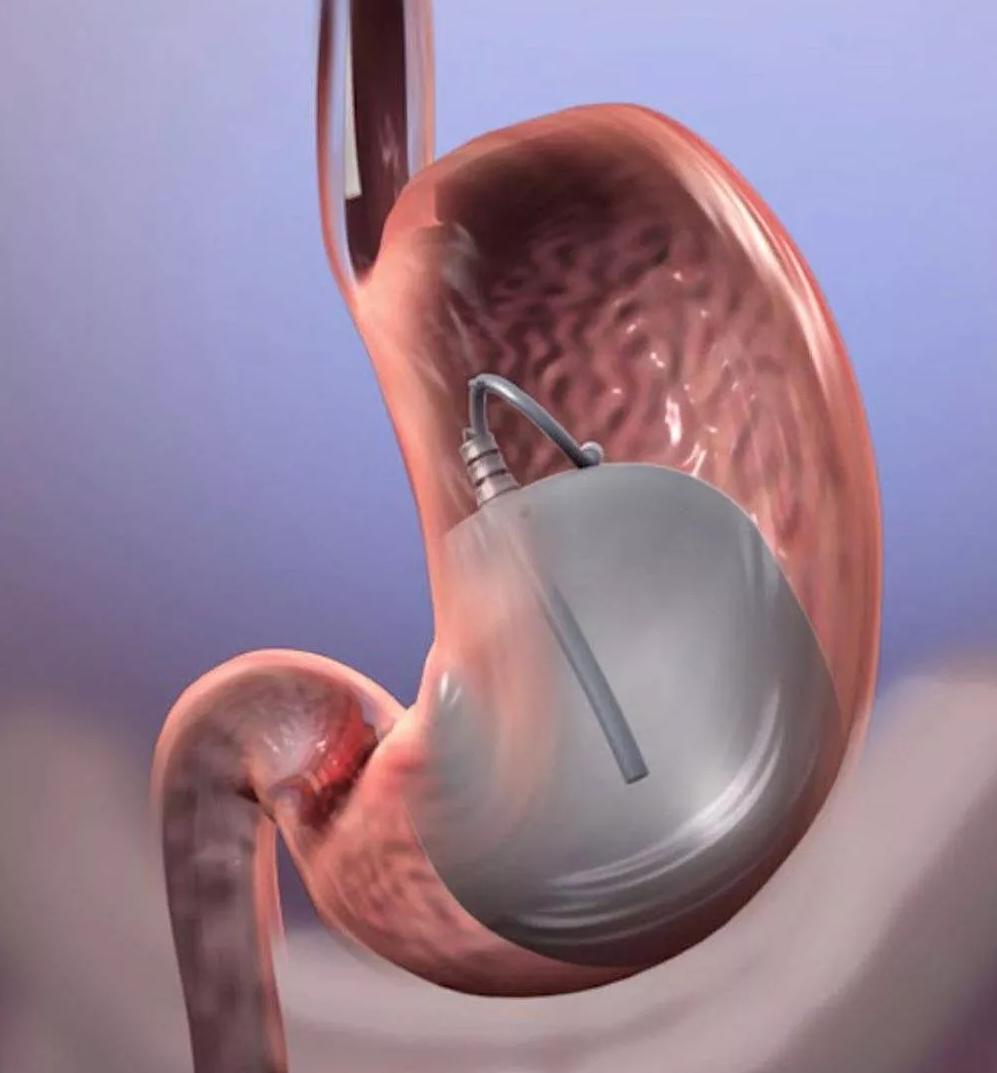

- Pneumatic dilation. A balloon is inserted by endoscopy into the center of the esophageal sphincter and inflated to enlarge the opening. This outpatient procedure may need to be repeated if the esophageal sphincter doesn't stay open. Nearly one-third of people treated with balloon dilation need repeat treatment within five years. This procedure requires sedation. (Image)

- Botox (botulinum toxin type A). This muscle relaxant can be injected directly into the esophageal sphincter with an endoscopic needle. The injections may need to be repeated, and repeat injections may make it more difficult to perform surgery later if needed. (Image)Botox is generally recommended only for people who aren't good candidates for pneumatic dilation or surgery due to age or overall health. Botox injections typically do not last more than six months. A strong improvement from injection of Botox may help confirm a diagnosis of achalasia.

Surgical Treatment

Surgical options for treating achalasia include:

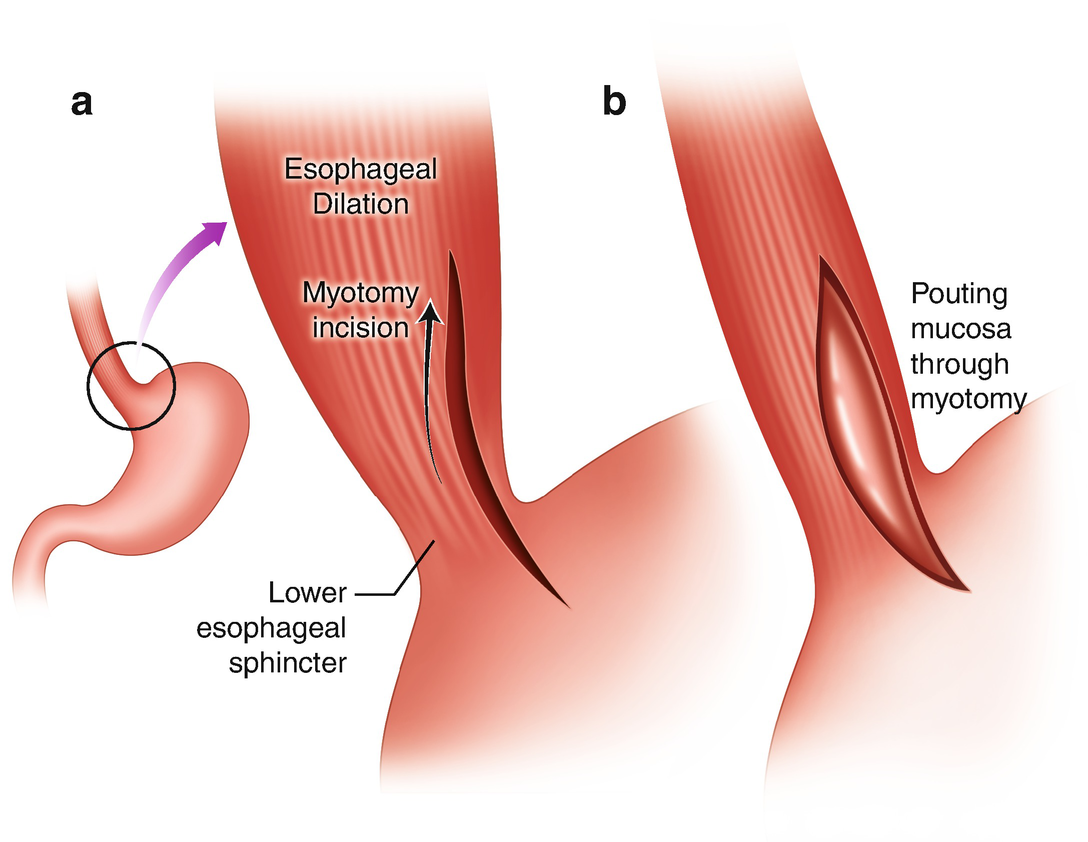

- Heller myotomy. The surgeon cuts the muscle at the lower end of the esophageal sphincter to allow food to pass more easily into the stomach. The procedure can be done noninvasively (laparoscopic Heller myotomy). Some people who have a Heller myotomy may later develop gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). To avoid future problems with GERD, a procedure known as fundoplication might be performed at the same time as a Heller myotomy. In fundoplication, the surgeon wraps the top of your stomach around the lower esophagus to create an anti-reflux valve, preventing acid from coming back (GERD) into the esophagus. Fundoplication is usually done with a minimally invasive (laparoscopic) procedure.

- Peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM). In the POEM procedure, the surgeon uses an endoscope inserted through your mouth and down your throat to create an incision in the inside lining of your esophagus. Then, as in a Heller myotomy, the surgeon cuts the muscle at the lower end of the esophageal sphincter. POEM may also be combined with or followed by later fundoplication to help prevent GERD. Some patients who have a POEM and develop GERD after the procedure are treated with daily oral medication.

_18574527625f9d2a23c8791.jpg)

Prevention

Researchers don’t know how to prevent achalasia.

Living with achalasia

Achalasia is a chronic condition. But you can manage it by working with your healthcare provider to create a treatment plan.

Your healthcare team will need to see you 1 or 2 times a year, even after your symptoms have lessened. You may need repeat endoscopy and esophogram procedures.

If you have symptoms of dysphagia or regurgitation:

- Stop smoking.

- Don’t eat foods or have drinks that give you heartburn.

- Drink plenty of fluids when eating. Chew your food well.

- Eat smaller meals more often.

- Don’t overeat late at night.

- If you have symptoms at night, prop up the head of your bed.