Hereditary Hemochromatosis

OVERVIEW | CAUSES | RISK FACTORS | SYMPTOMS | COMPLICATION | DIAGNOSIS | TREATMENT | PREVENTION | REFERENCES

OVERVIEW

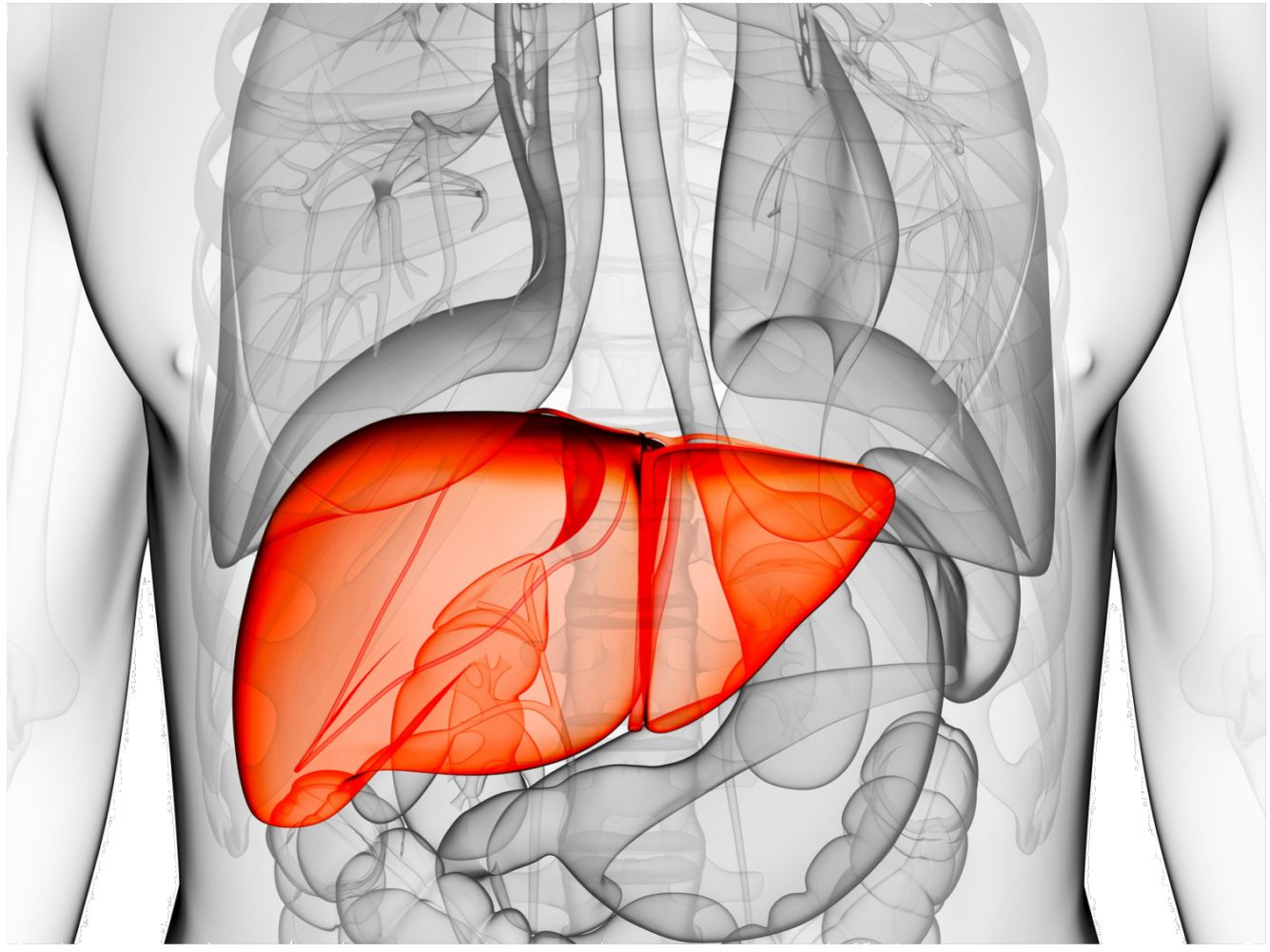

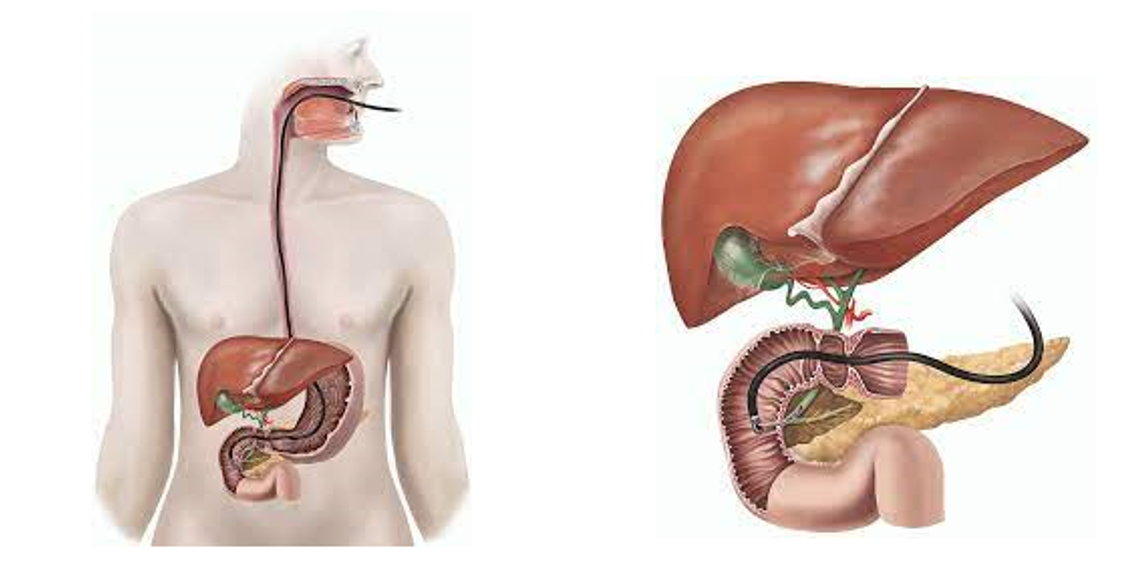

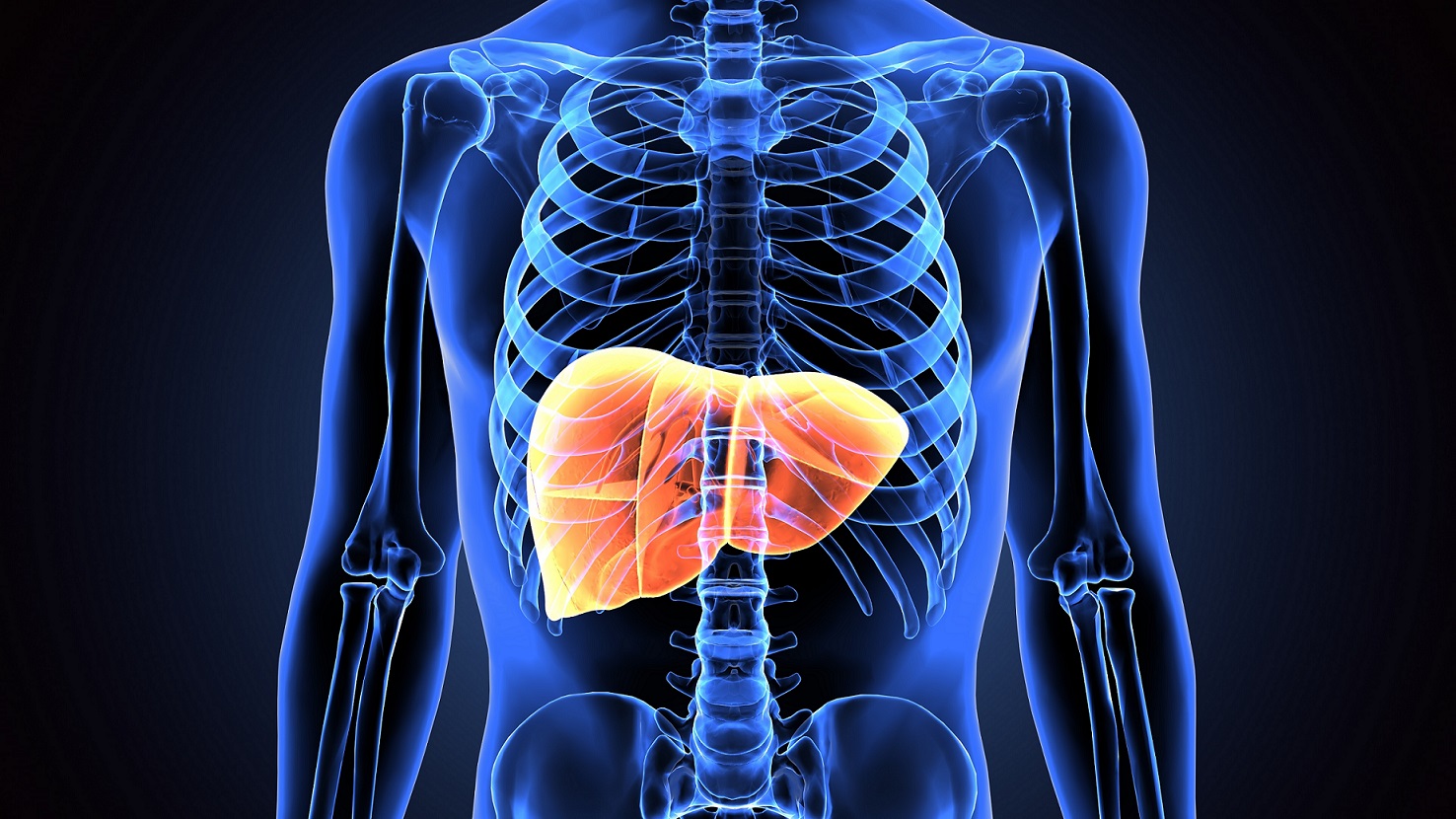

Hereditary hemochromatosis causes your body to absorb too much iron from the food you eat. Excess iron is stored in your organs, especially your liver, heart and pancreas. Too much iron can lead to life-threatening conditions, such as liver disease, heart problems and diabetes.

The genes that cause hemochromatosis are inherited, but only a minority of people who have the genes ever develop serious problems. Signs and symptoms of hereditary hemochromatosis usually appear in midlife.

Treatment includes regularly removing blood from your body. Because much of the body's iron is contained in red blood cells, this treatment lowers iron levels.

CAUSES

Hereditary hemochromatosis is caused by a mutation in a gene that controls the amount of iron your body absorbs from the food you eat. These mutations are passed from parents to children. This type of hemochromatosis is by far the most common type.

Gene mutations that cause hemochromatosis

A gene called HFE is most often the cause of hereditary hemochromatosis. You inherit one HFE gene from each of your parents. The HFE gene has two common mutations, C282Y and H63D. Genetic testing can reveal whether you have these mutations in your HFE gene.

- If you inherit 2 abnormal genes, you may develop hemochromatosis. You can also pass the mutation on to your children. But not everyone who inherits two genes develops problems linked to the iron overload of hemochromatosis.

- If you inherit 1 abnormal gene, you're unlikely to develop hemochromatosis. However, you are considered a gene mutation carrier and can pass the mutation on to your children. But your children wouldn't develop the disease unless they also inherited another abnormal gene from the other parent.

RISK FACTORS

Factors that increase your risk of hereditary hemochromatosis include:

- Having 2 copies of a mutated HFE gene. This is the greatest risk factor for hereditary hemochromatosis.

- Family history. If you have a first-degree relative — a parent or sibling — with hemochromatosis, you're more likely to develop the disease.

- Ethnicity. People of Northern European descent are more prone to hereditary hemochromatosis than are people of other ethnic backgrounds. Hemochromatosis is less common in people of Black, Hispanic and Asian ancestry.

- Your sex. Men are more likely than women to develop signs and symptoms of hemochromatosis at an earlier age. Because women lose iron through menstruation and pregnancy, they tend to store less of the mineral than men do. After menopause or a hysterectomy, the risk for women increases.

SYMPTOMS

Some people with hereditary hemochromatosis never have symptoms. Early signs and symptoms often overlap with those of other common conditions.

Signs and symptoms may include:

- Joint pain

- Abdominal pain

- Fatigue

- Weakness

- Diabetes

- Loss of sex drive

- Impotence

- Heart failure

- Liver failure

- Bronze or gray skin color

- Memory fog

When signs and symptoms typically appear

Hereditary hemochromatosis is present at birth. But most people don't experience signs and symptoms until later in life — usually after the age of 40 in men and after age 60 in women. Women are more likely to develop symptoms after menopause, when they no longer lose iron with menstruation and pregnancy.

COMPLICATIONS

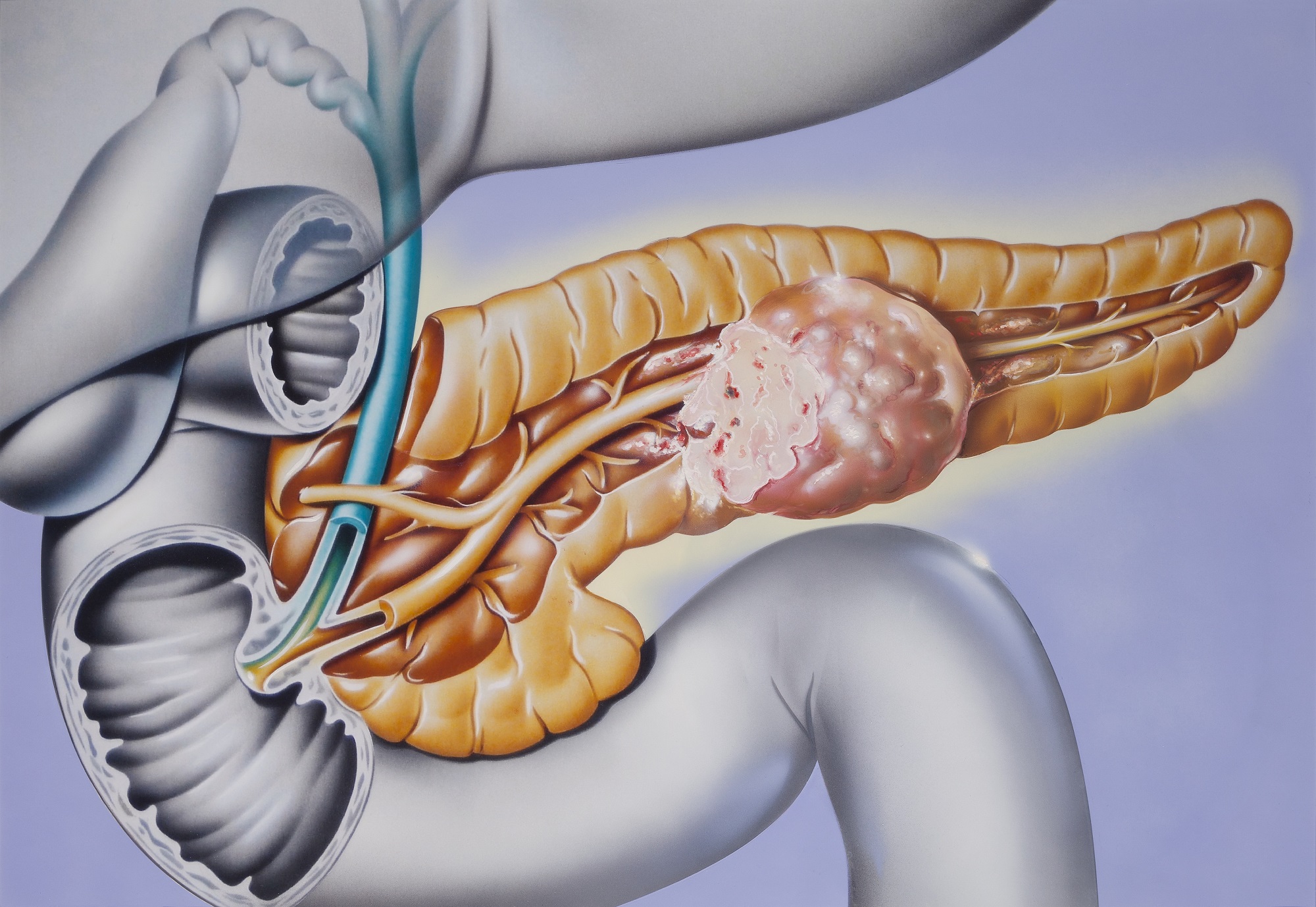

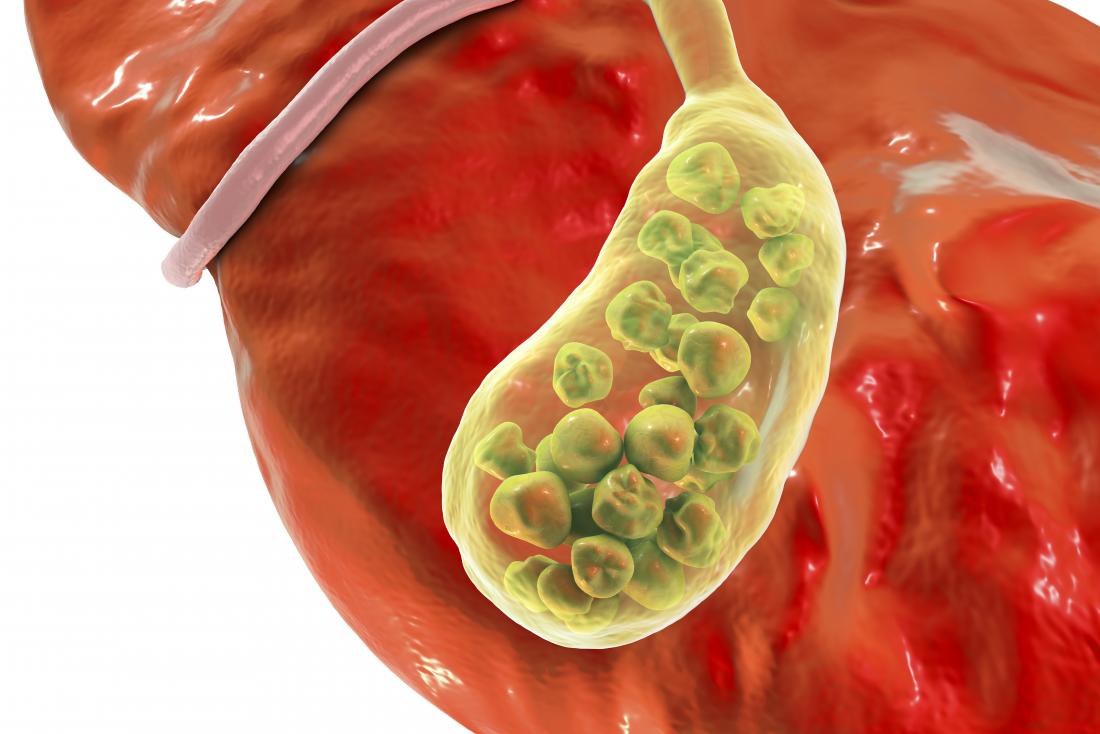

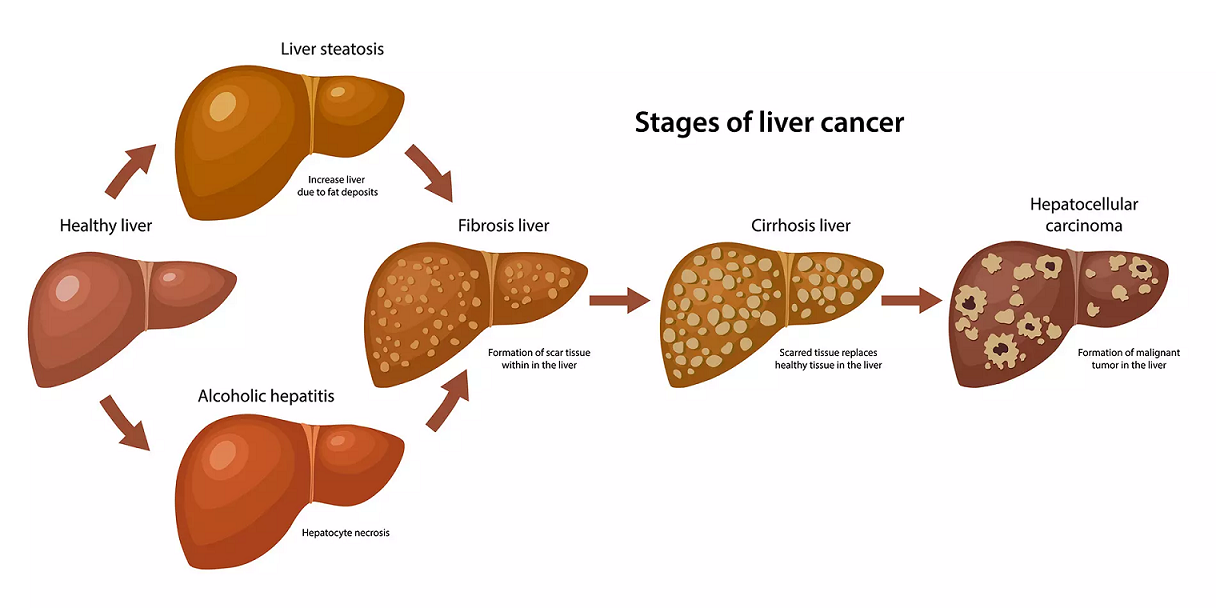

Untreated, hereditary hemochromatosis can lead to a number of complications, especially in your joints and in organs where excess iron tends to be stored — your liver, pancreas and heart. Complications can include:

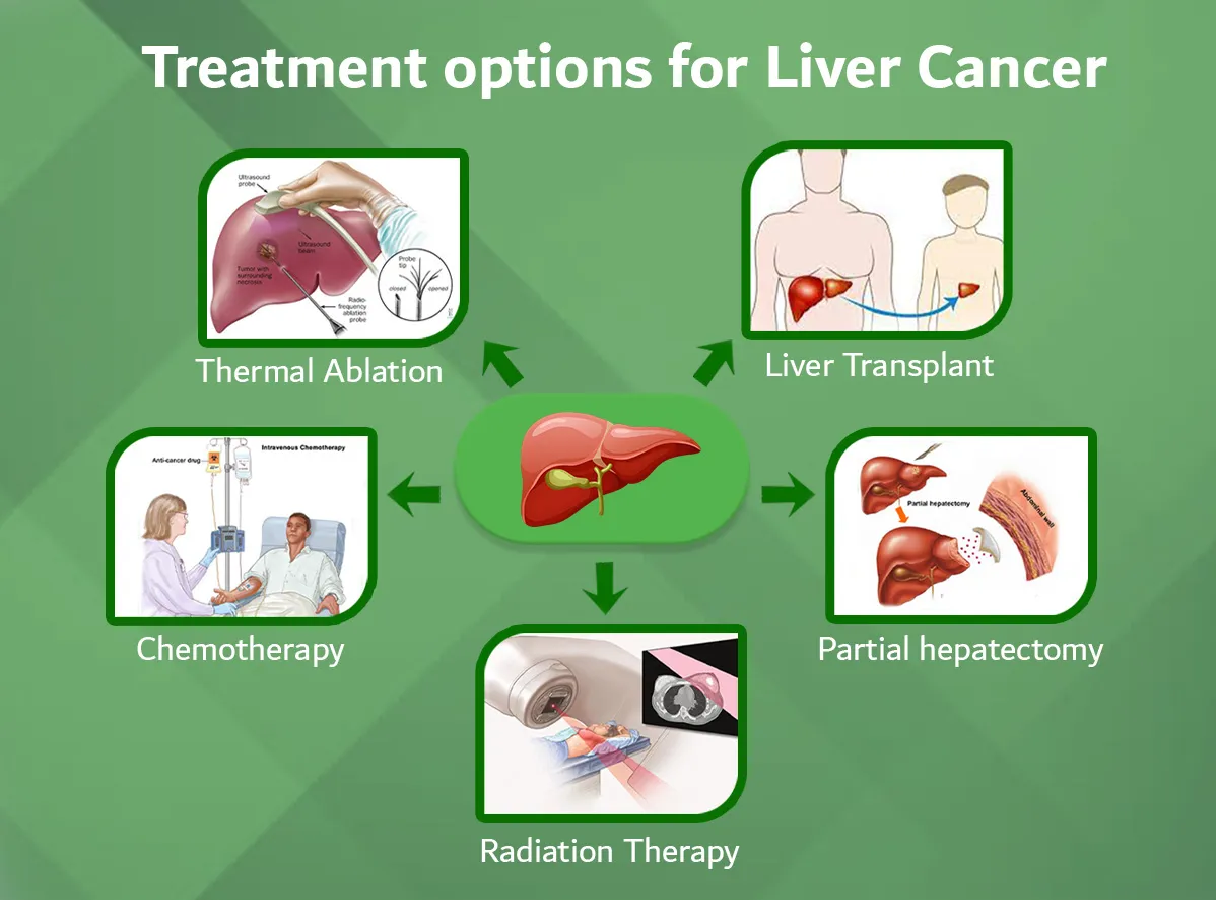

- Liver problems. Cirrhosis- permanent scarring of the liver- is just one of the problems that may occur. Cirrhosis increases your risk of liver cancer and other life-threatening complications.

- Diabetes. Damage to the pancreas can lead to diabetes.

- Heart problems. Excess iron in your heart affects the heart's ability to circulate enough blood for your body's needs. This is called congestive heart failure. Hemochromatosis can also cause abnormal heart rhythms (arrhythmias).

- Reproductive problems. Excess iron can lead to erectile dysfunction (impotence), and loss of sex drive in men and absence of the menstrual cycle in women.

- Skin color changes. Deposits of iron in skin cells can make your skin appear bronze or gray in color.

DIAGNOSIS

Hereditary hemochromatosis can be difficult to diagnose. Early symptoms such as stiff joints and fatigue may be due to conditions other than hemochromatosis.

Many people with the disease don't have any signs or symptoms other than elevated levels of iron in their blood. Hemochromatosis may be identified because of abnormal blood tests done for other reasons or from screening of family members of people diagnosed with the disease.

Blood tests

The two key tests to detect iron overload are:

- Serum transferrin saturation. This test measures the amount of iron bound to a protein (transferrin) that carries iron in your blood. Transferrin saturation values greater than 45% are considered too high.

- Serum ferritin. This test measures the amount of iron stored in your liver. If the results of your serum transferrin saturation test are higher than normal, your doctor will check your serum ferritin.

Because a number of other conditions can also cause elevated ferritin, both blood tests are typically abnormal among people with this disorder and are best performed after you have been fasting. Elevations in one or all of these blood tests for iron can be found in other disorders. You may need to have the tests repeated for the most accurate results.

Additional testing

Your doctor may suggest other tests to confirm the diagnosis and to look for other problems:

- Liver function tests. These tests can help identify liver damage.

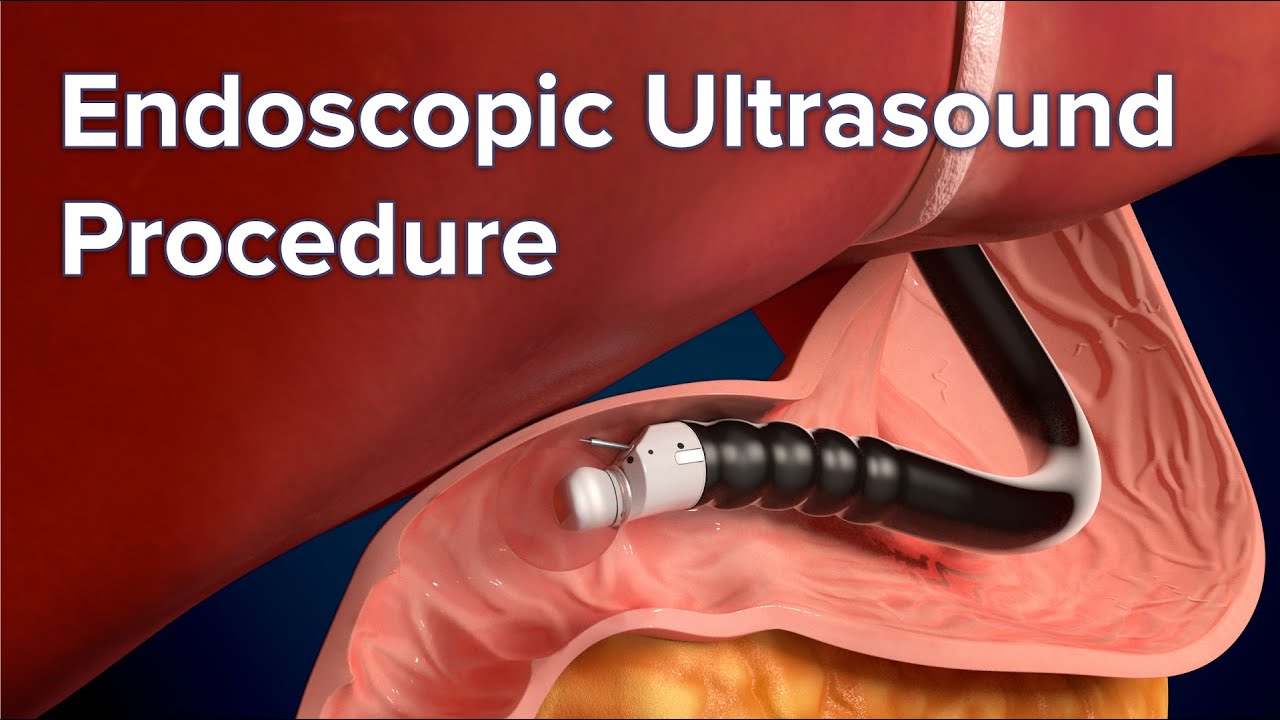

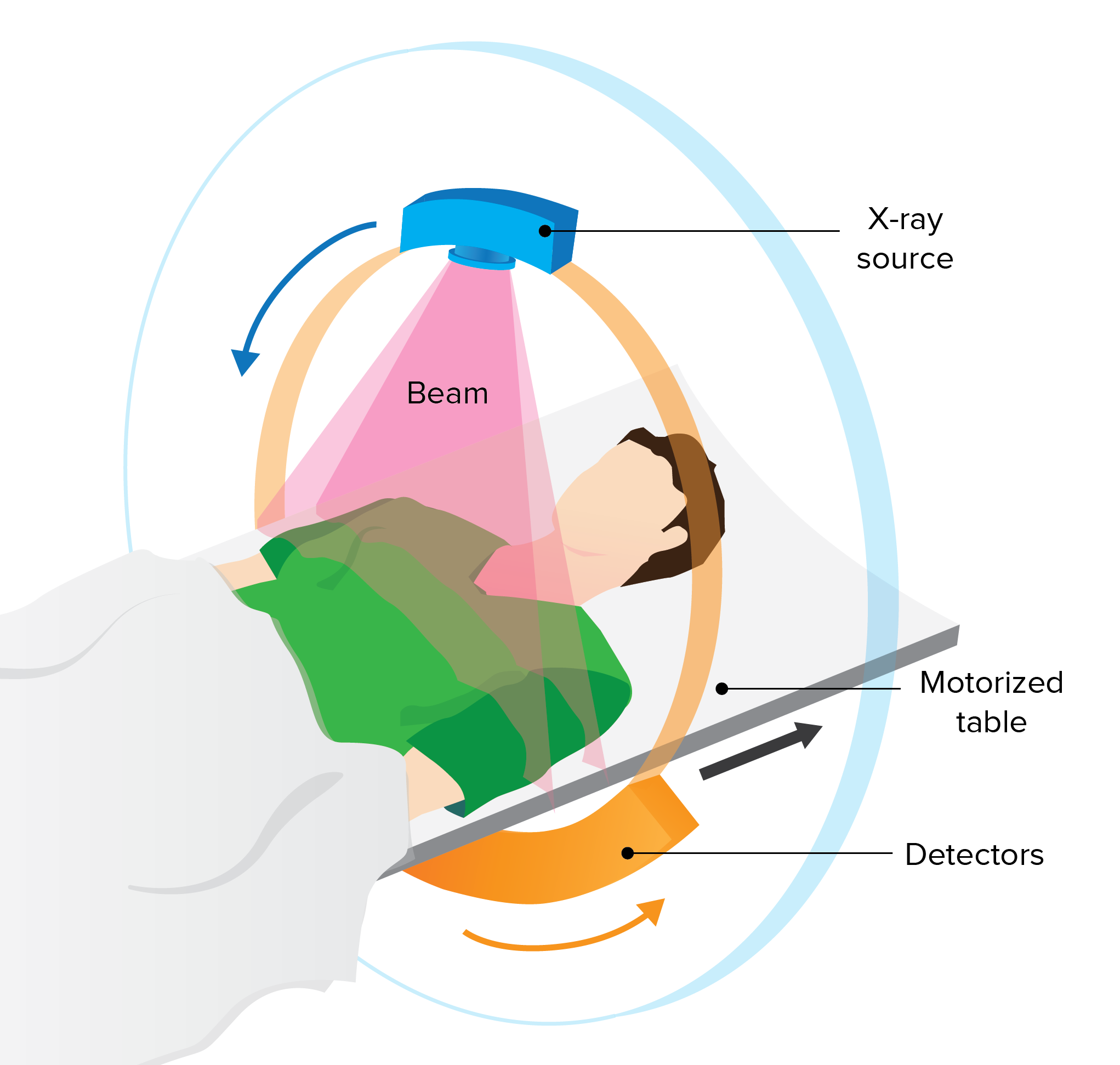

- MRI. An MRI is a fast and noninvasive way to measure the degree of iron overload in your liver.

- Testing for gene mutations. Testing your DNA for mutations in the HFE gene is recommended if you have high levels of iron in your blood. If you're considering genetic testing for hemochromatosis, discuss the pros and cons with your doctor or a genetic counselor.

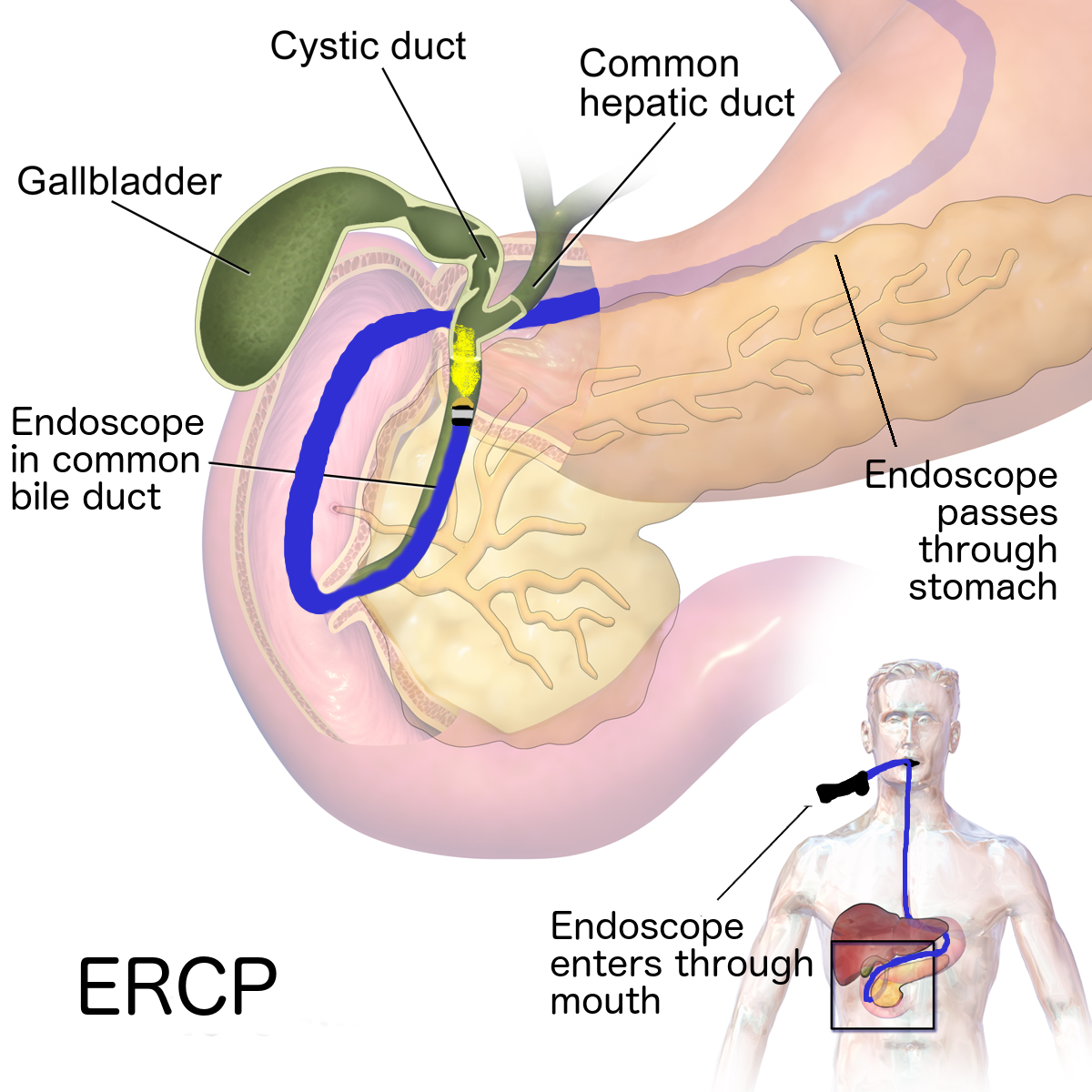

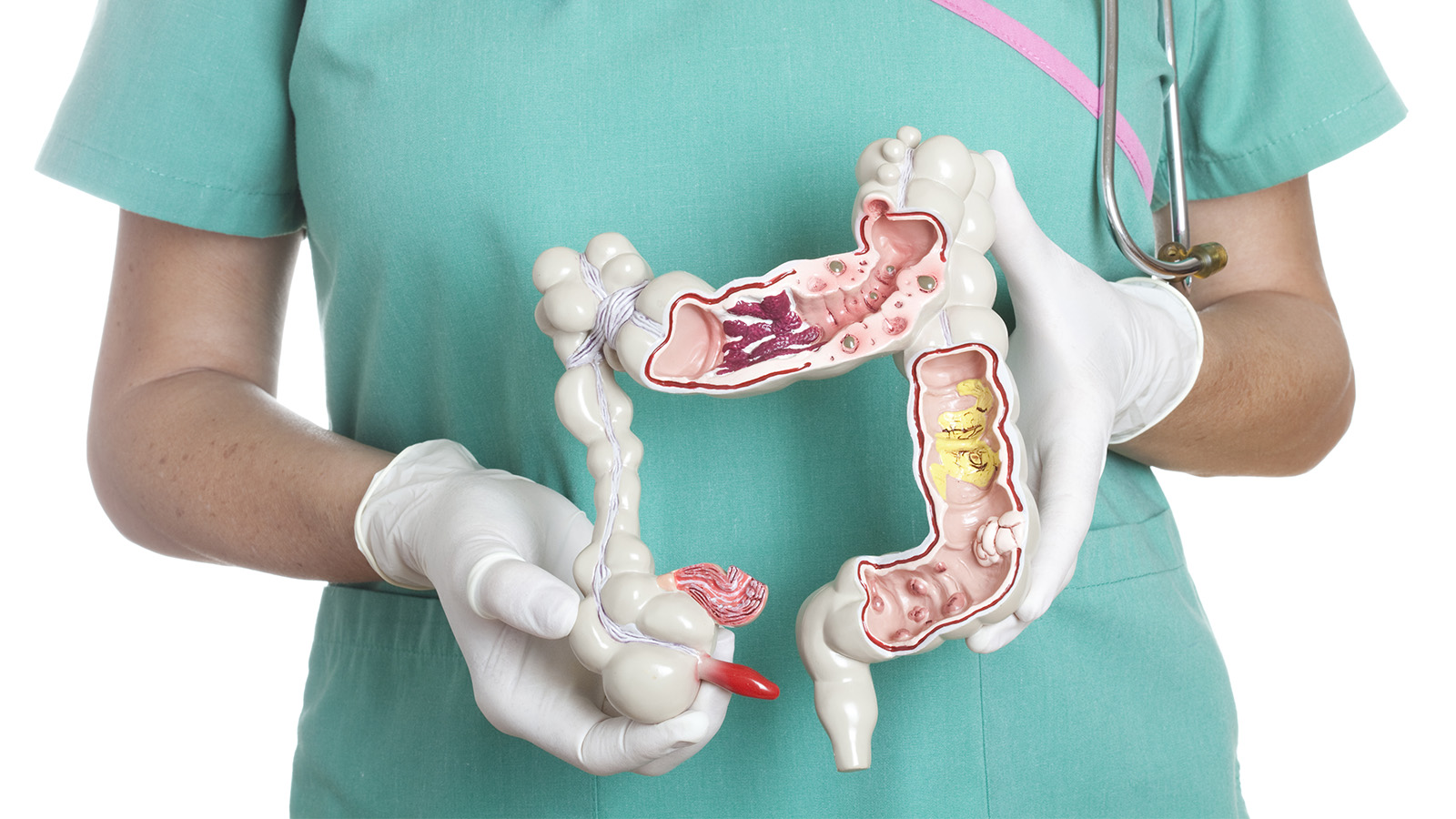

- Removing a sample of liver tissue for testing (liver biopsy). If liver damage is suspected, your doctor may have a sample of tissue from your liver removed, using a thin needle. The sample is sent to a laboratory to be checked for the presence of iron as well as for evidence of liver damage, especially scarring or cirrhosis. Risks of biopsy include bruising, bleeding and infection.

Screening healthy people for hemochromatosis

Genetic testing is recommended for all first-degree relatives- parents, siblings and children- of anyone diagnosed with hemochromatosis. If a mutation is found in only one parent, then children do not need to be tested.

TREATMENT

Blood removal

Doctors can treat hereditary hemochromatosis safely and effectively by removing blood from your body (phlebotomy) on a regular basis, just as if you were donating blood.

The goal of phlebotomy is to reduce your iron levels to normal. The amount of blood removed and how often it's removed depend on your age, your overall health and the severity of iron overload.

- Initial treatment schedule. Initially, you may have a pint (about 470 milliliters) of blood taken once or twice a week — usually in a hospital or your doctor's office. While you recline in a chair, a needle is inserted into a vein in your arm. The blood flows from the needle into a tube that's attached to a blood bag.

- Maintenance treatment schedule. Once your iron levels have returned to normal, blood can be removed less often, typically every two to three months. Some people may maintain normal iron levels without having any blood taken, and some may need to have blood removed monthly. The schedule depends on how rapidly iron accumulates in your body.

Treating hereditary hemochromatosis can help alleviate symptoms of tiredness, abdominal pain and skin darkening. It can help prevent serious complications such as liver disease, heart disease and diabetes. If you already have one of these conditions, phlebotomy may slow the progression of the disease, and in some cases even reverse it.

Phlebotomy will not reverse cirrhosis or joint pain, but it can slow the progression.

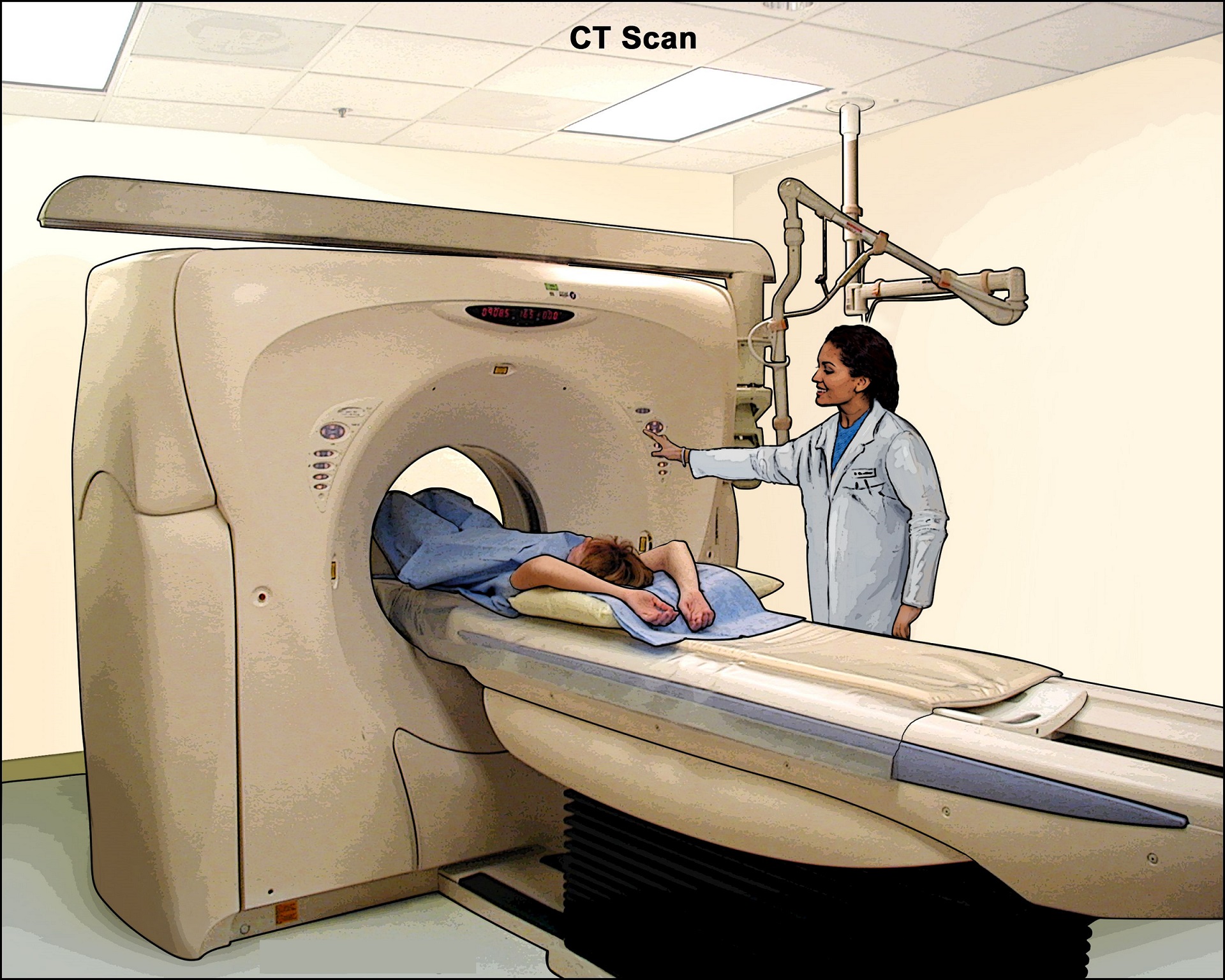

If you have cirrhosis, your doctor may recommend periodic screening for liver cancer. This usually involves an abdominal ultrasound and CT scan.

Chelation for those who can't undergo blood removal

If you can't undergo phlebotomy, because you have anemia, for example, or heart complications, your doctor may recommend a medication to remove excess iron. The medication can be injected into your body, or it can be taken as a pill. The medication binds excess iron, allowing your body to expel iron through your urine or stool in a process that's called chelation. Chelation is not commonly used in hereditary hemochromatosis.

You can't prevent primary, or inherited, hemochromatosis. However, not everyone who inherits hemochromatosis genes develops symptoms or complications of the disease. In those who do, treatments can keep the disease from getting worse.

REFERENCE

- https://www.cdc.gov/genomics/disease/hemochromatosis.htm

- https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/hemochromatosis/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430862/

- https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/condition/hereditary-hemochromatosis/