Diabetes

New hope for cure of type 1 Diabetes by Stem Cell Therapy

While diabetes can be treated and controlled, no cure currently exists. But thanks to a new treatment using stem cells that produce insulin, a new cure could be possible within the next decade.

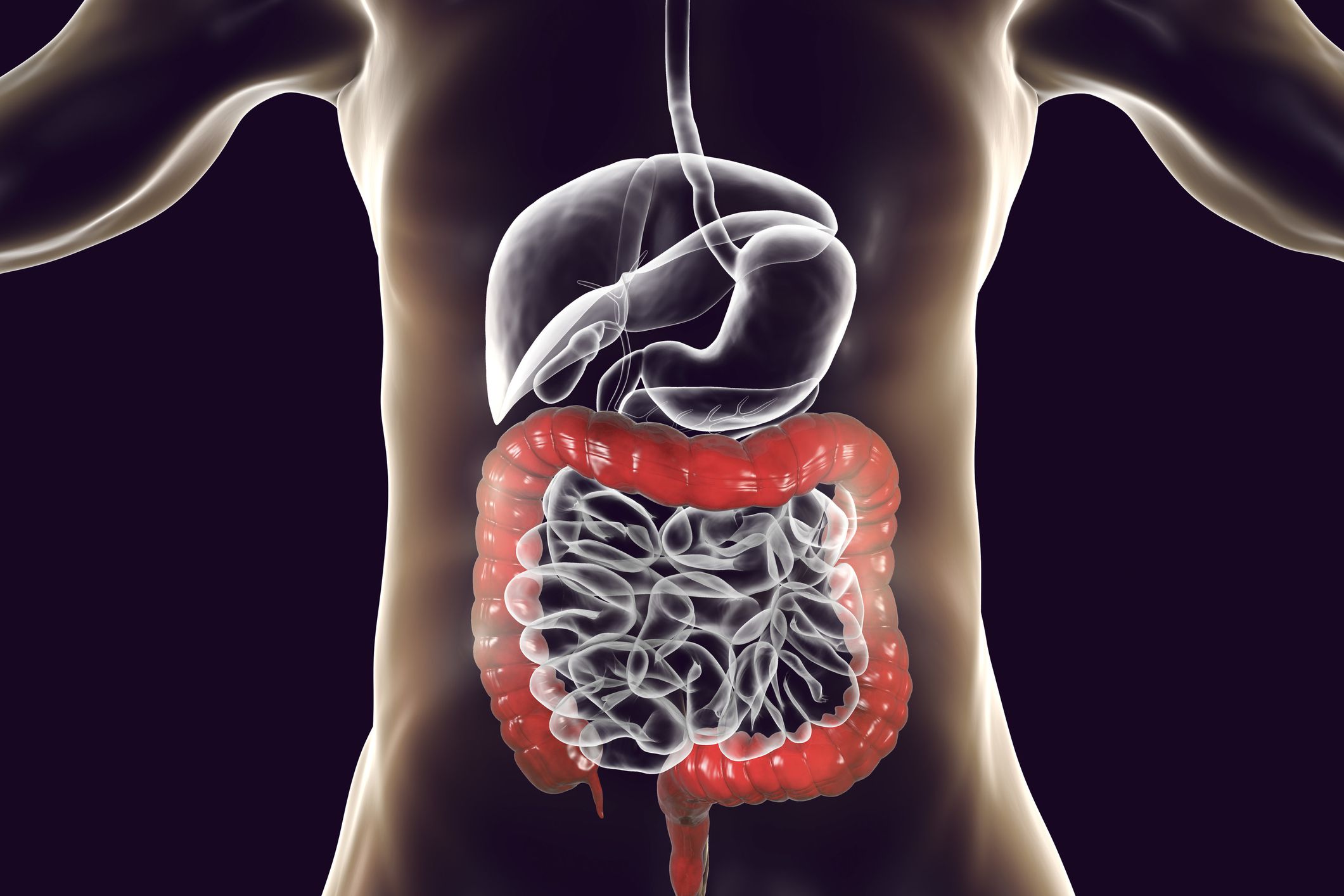

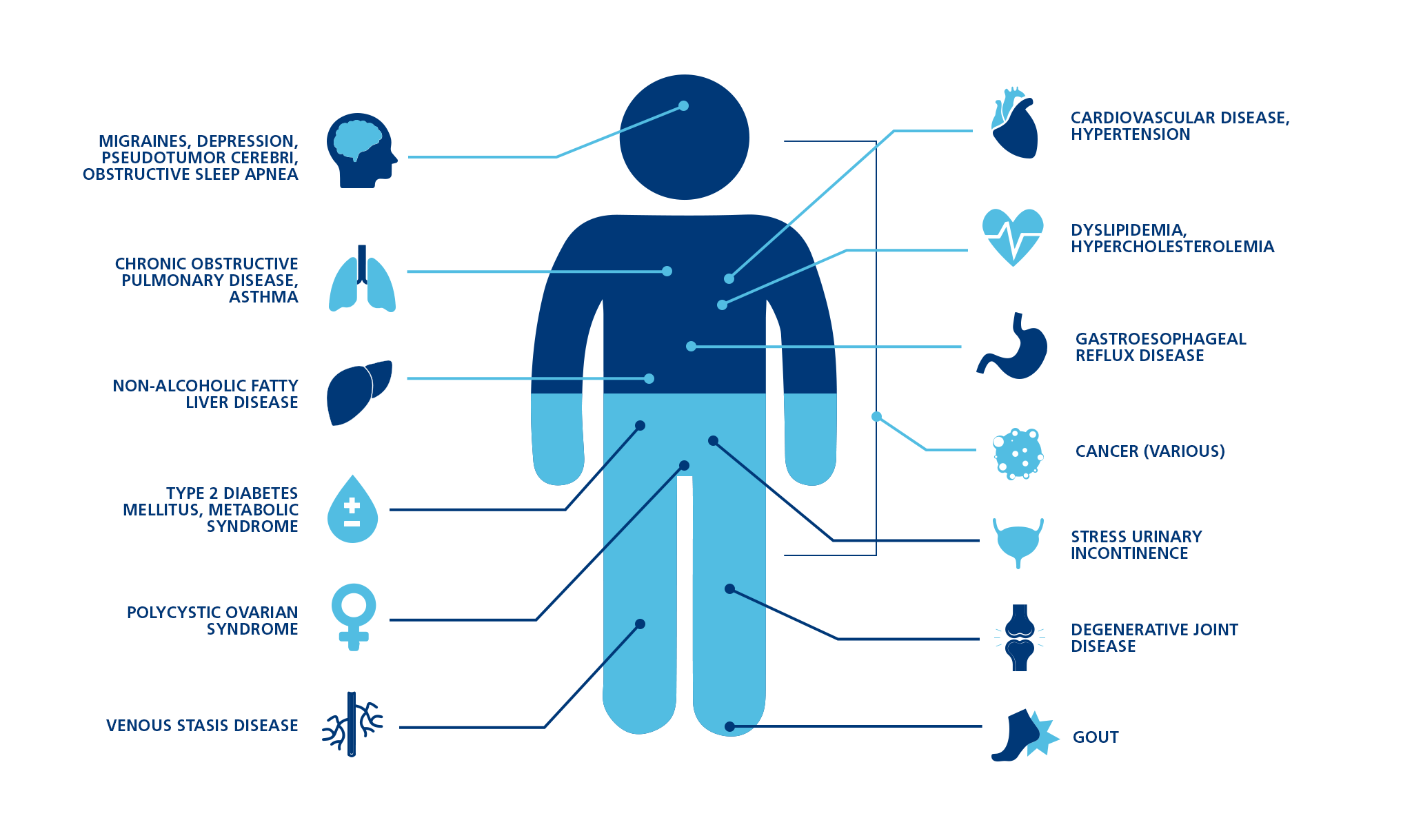

An estimated 11.8% of the Indian population has been diagnosed with diabetes (source), a number that may be apt to rise in the near future. Researchers have also found a link between contracting COVID-19 and an increased risk of receiving a diabetes diagnosis months later- especially in children, as one study showed that COVID-19 receptors can reduce insulin levels and kill pancreatic beta cells. (source)

While there is still much to learn about the connection between COVID-19 and diabetes, a potential wave of diabetes infections comes at an unprecedented time for the disease- perhaps when a cure is on the horizon.

For so long, there were only treatments to keep diabetes in check with it being one of the most expensive, consuming and pervasive chronic diseases. But now researchers are inching towards a cure, to the extent that they are actually openly using that word.

In November 2021, news broke that Brian Shelton, a 64-year-old man in Ohio, might be the first person to ever be cured of type 1 diabetes. (source) Shelton was part of a clinical trial by Vertex Pharmaceuticals, in which participants individually receive an infusion of stem cells that in turn create the insulin-producing pancreas cells the body lacks with Type 1 diabetes. In total, the study will take five years and only involve 17 people with severe cases of Type 1 diabetes.

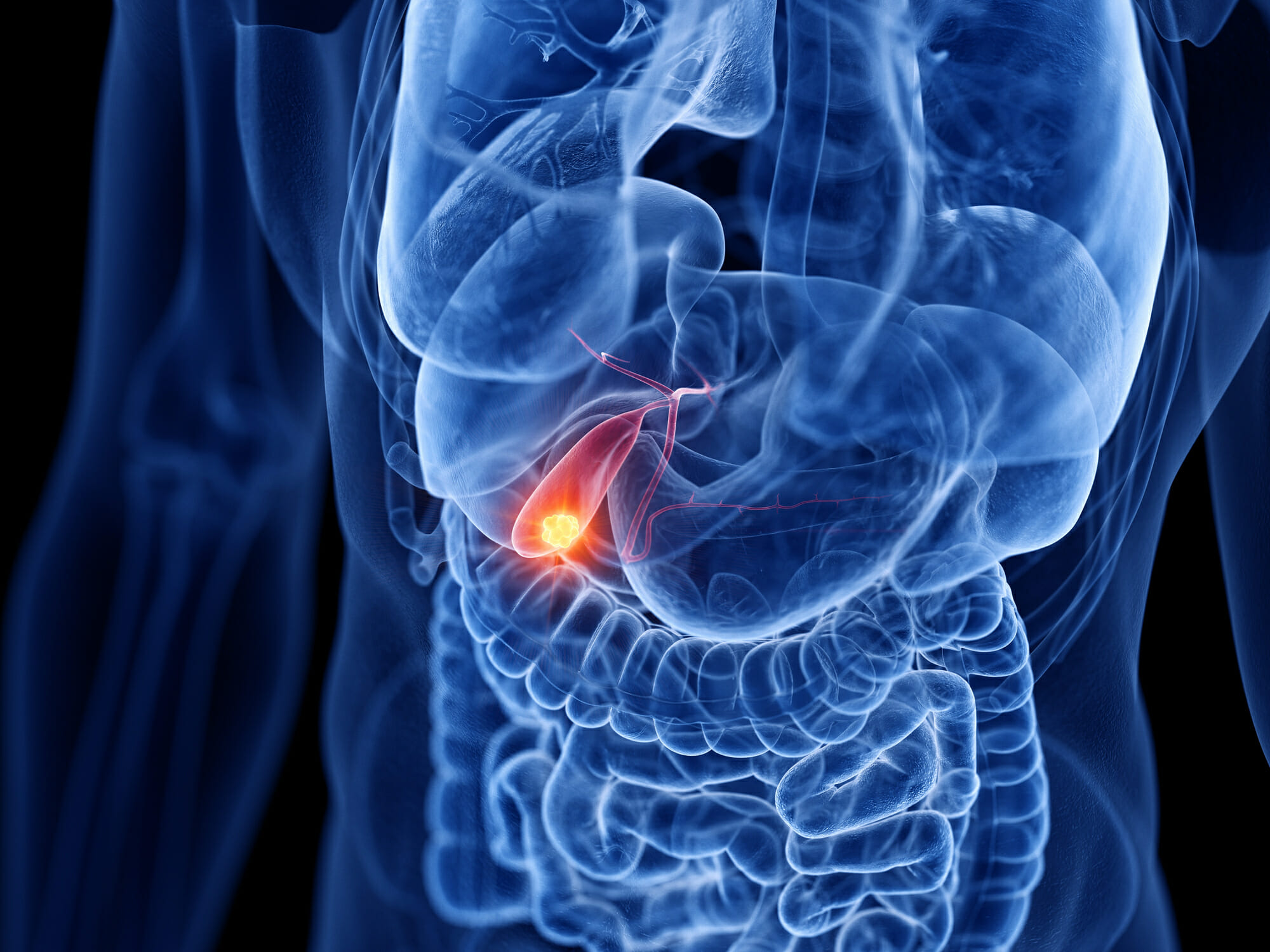

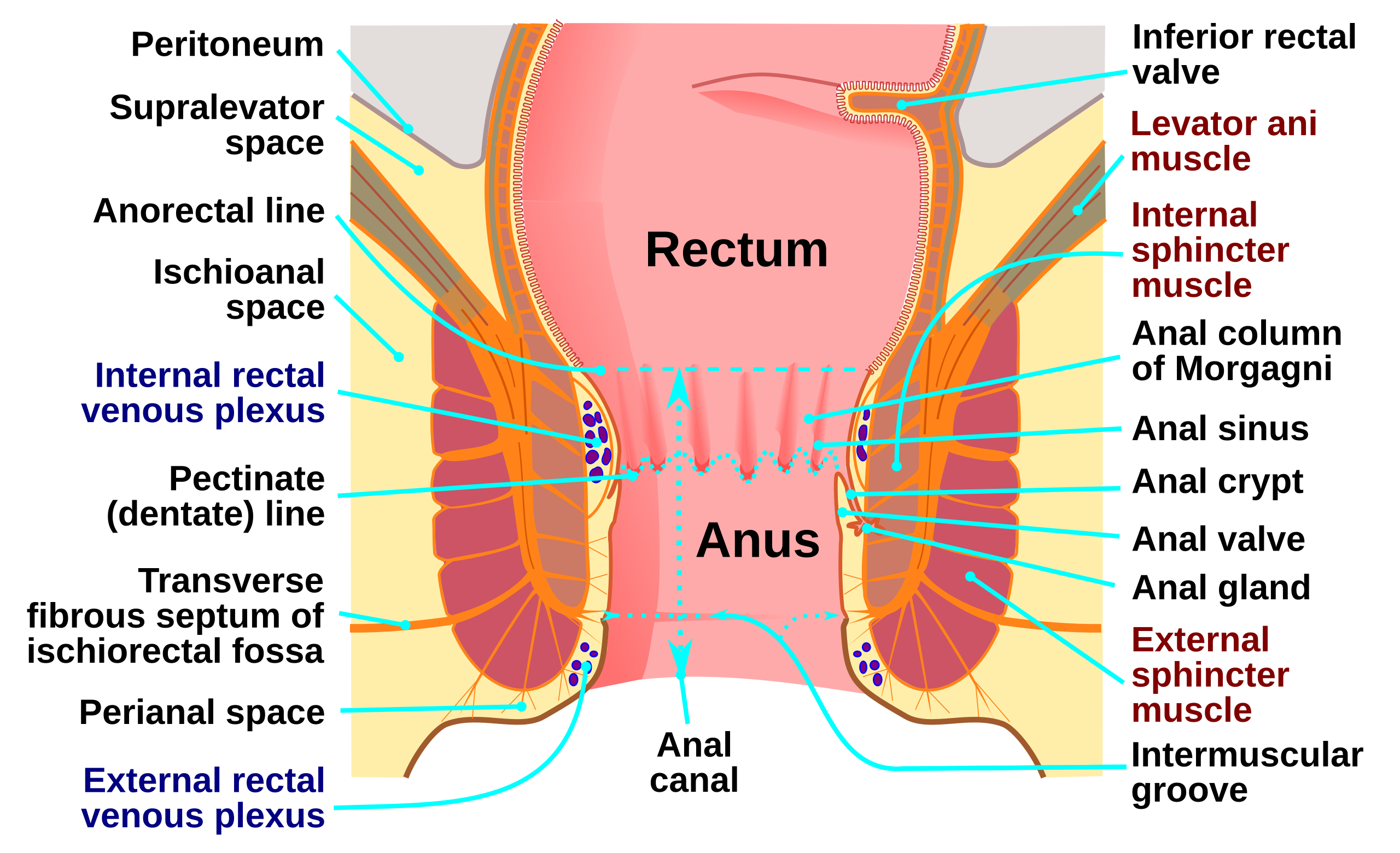

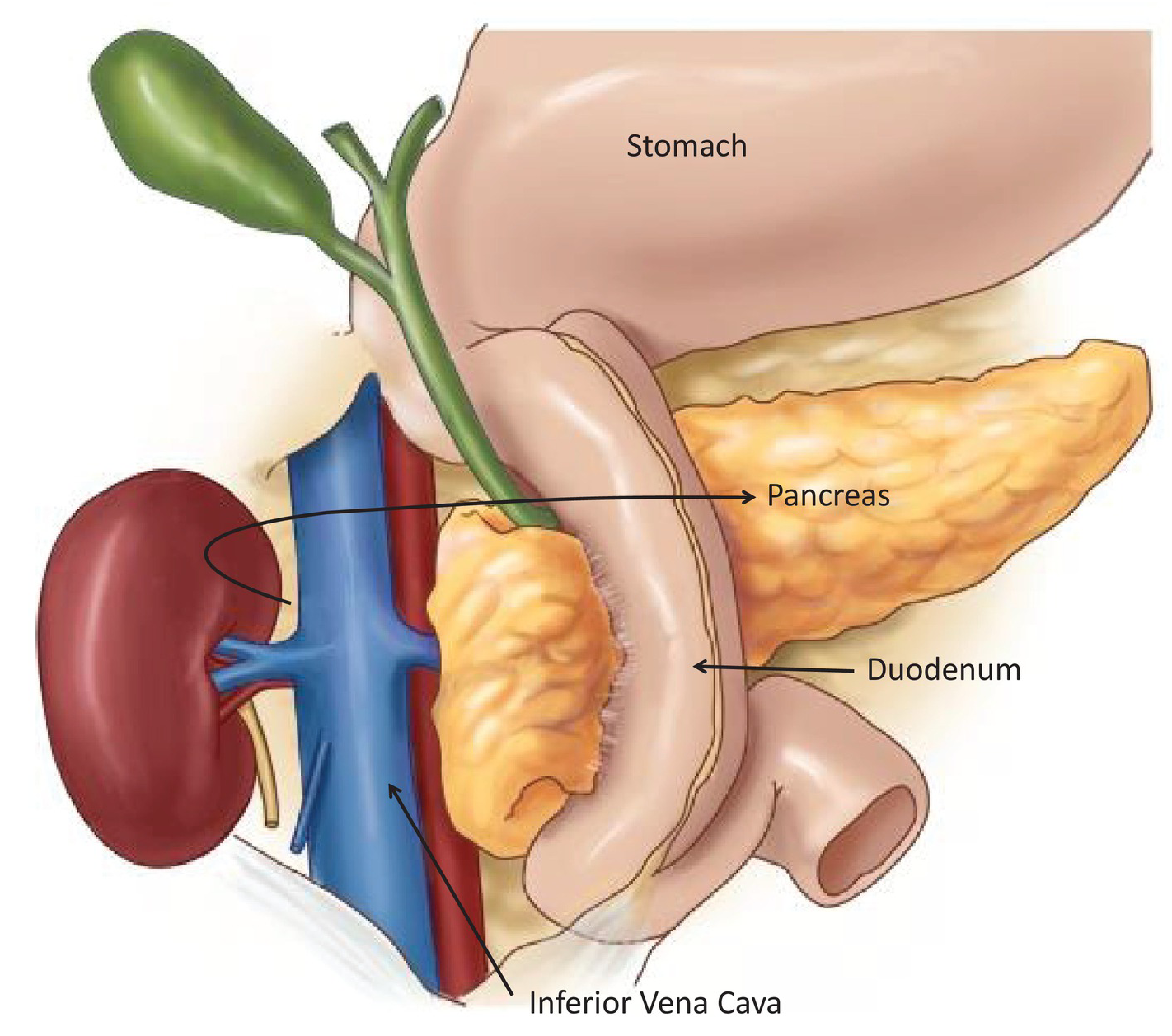

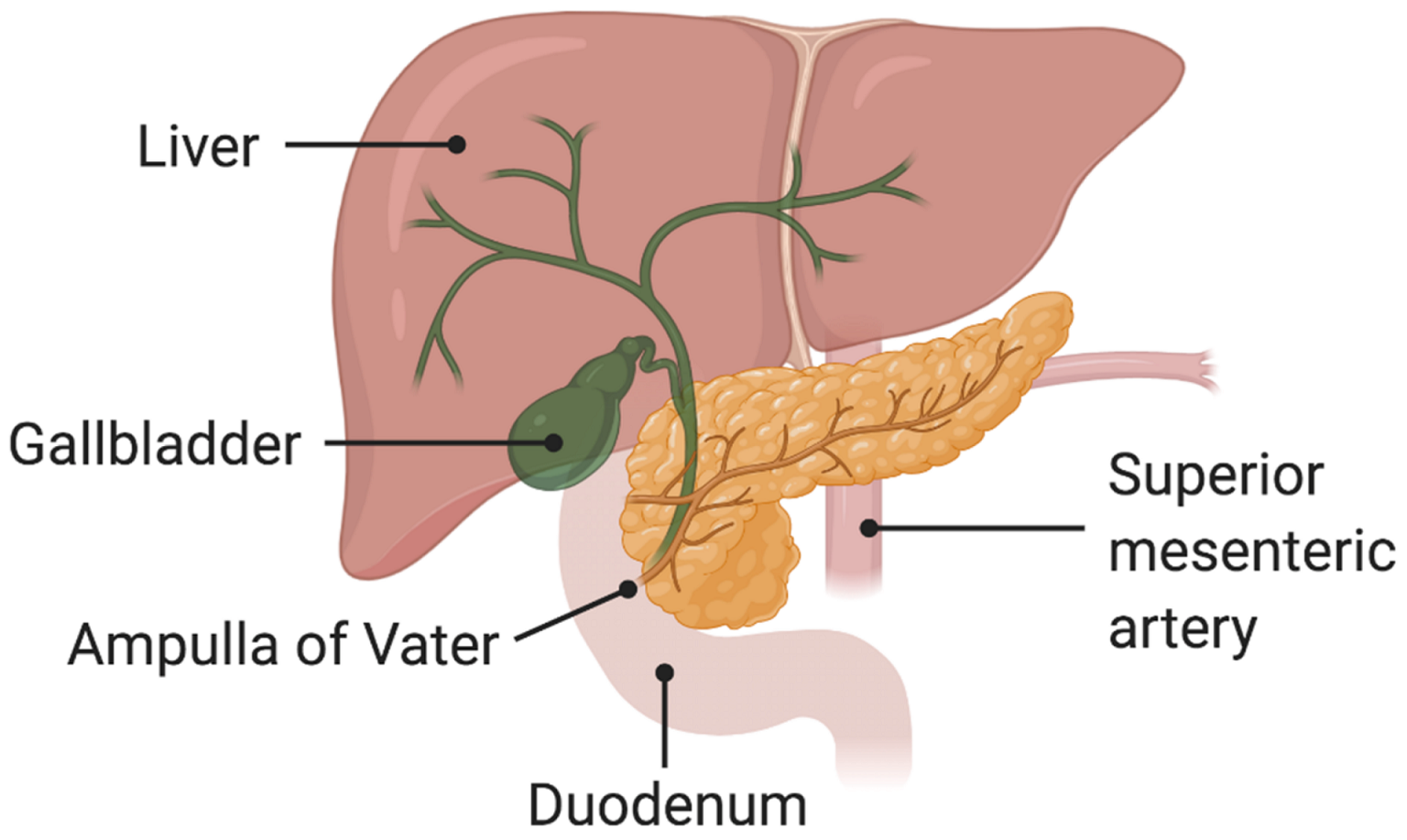

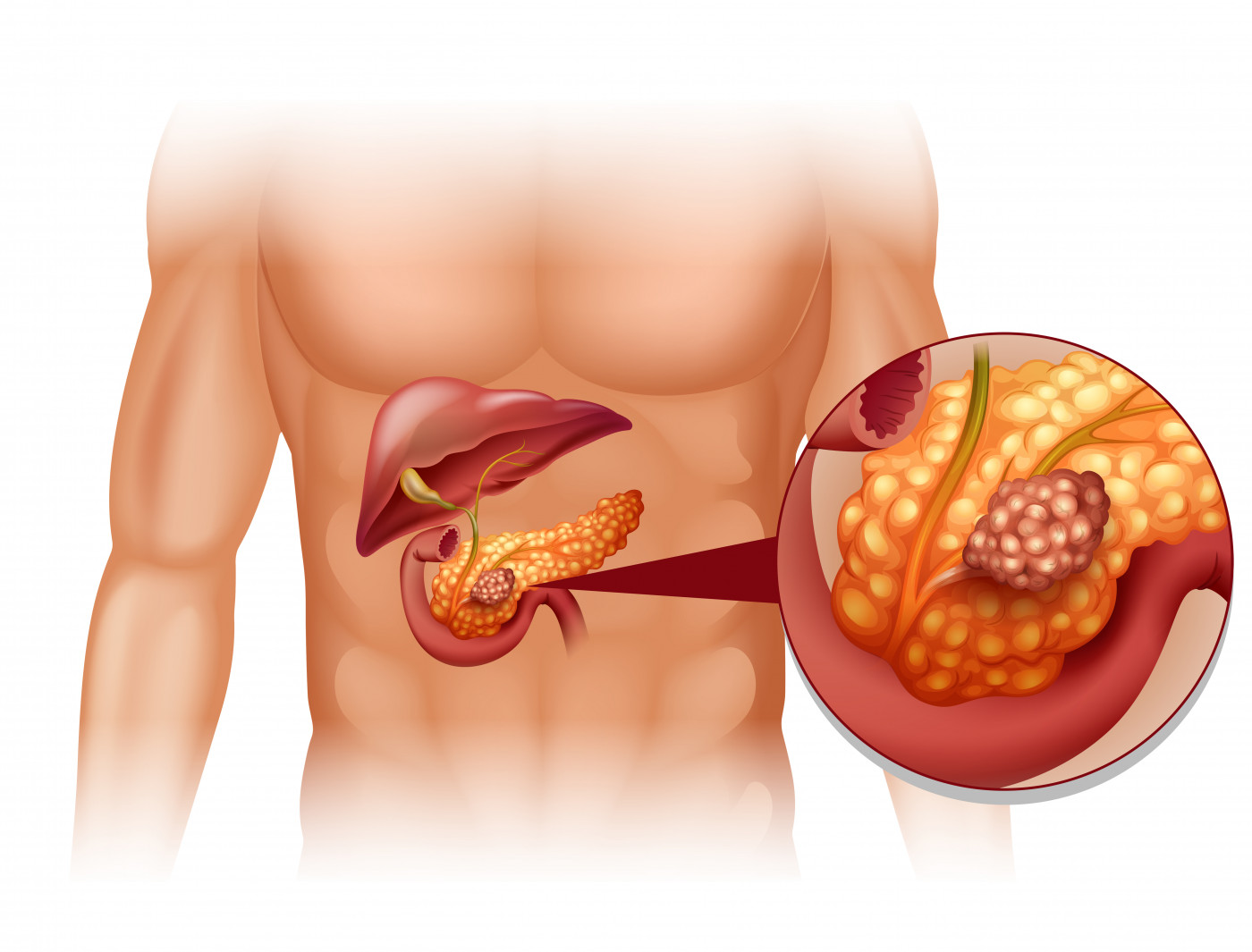

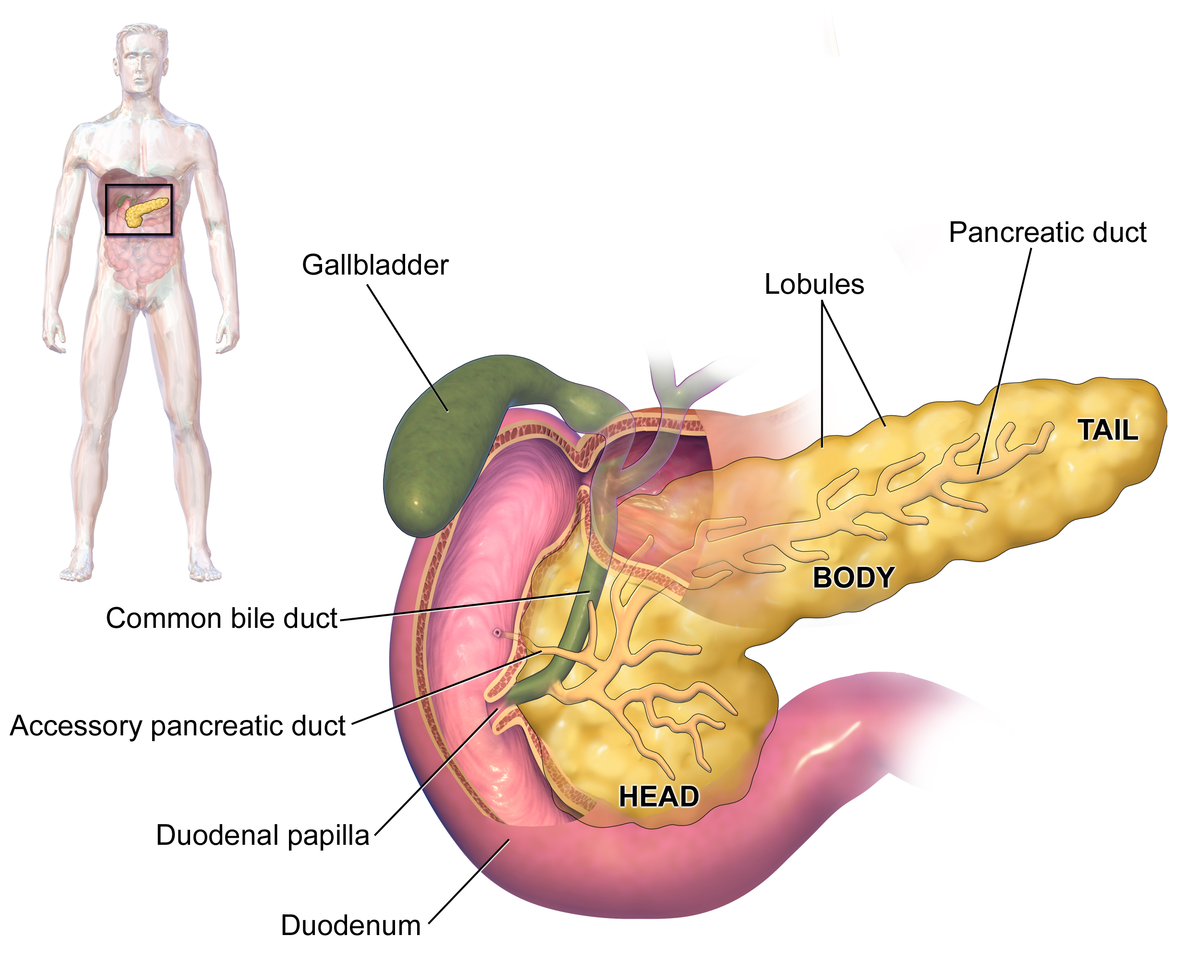

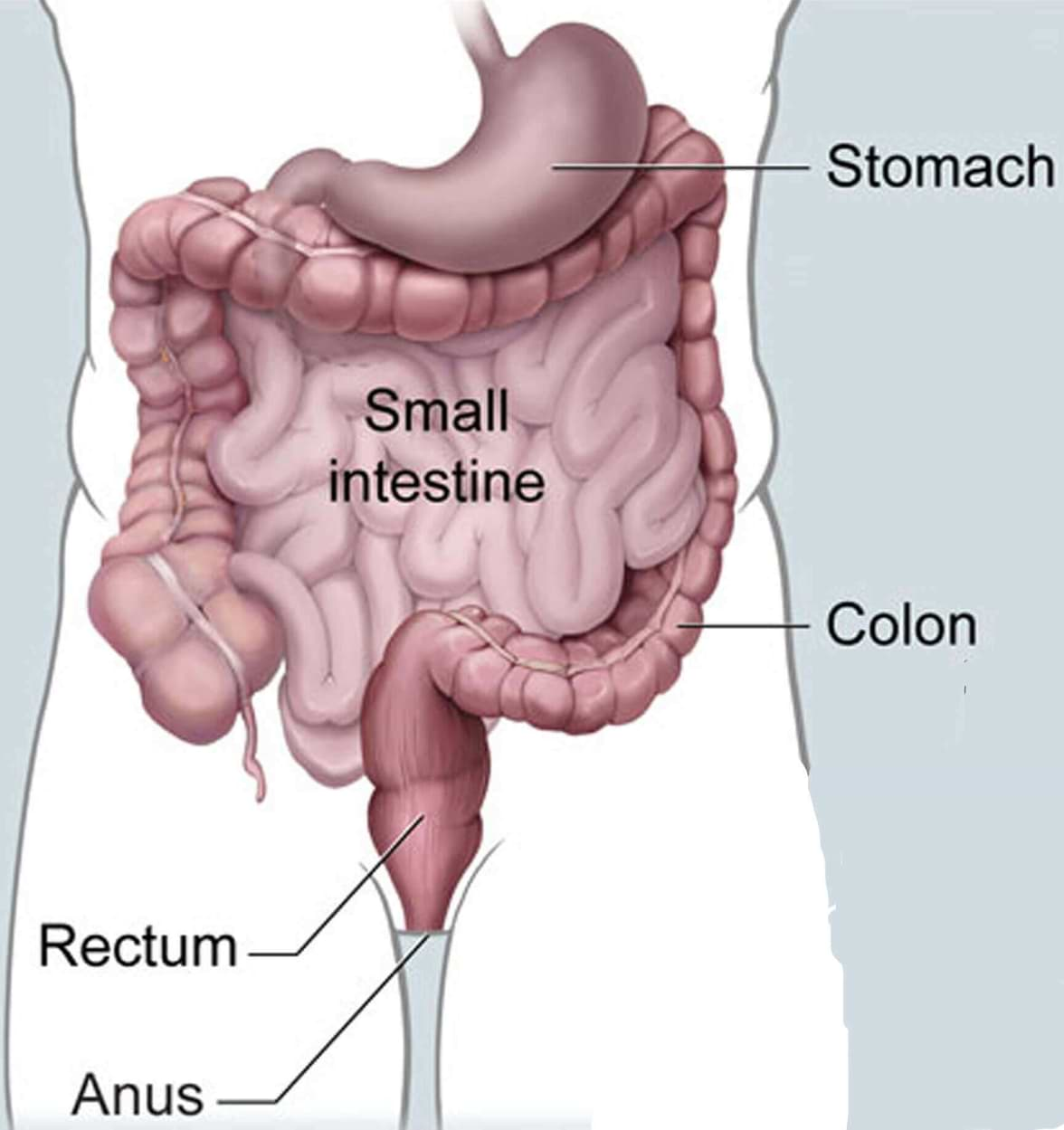

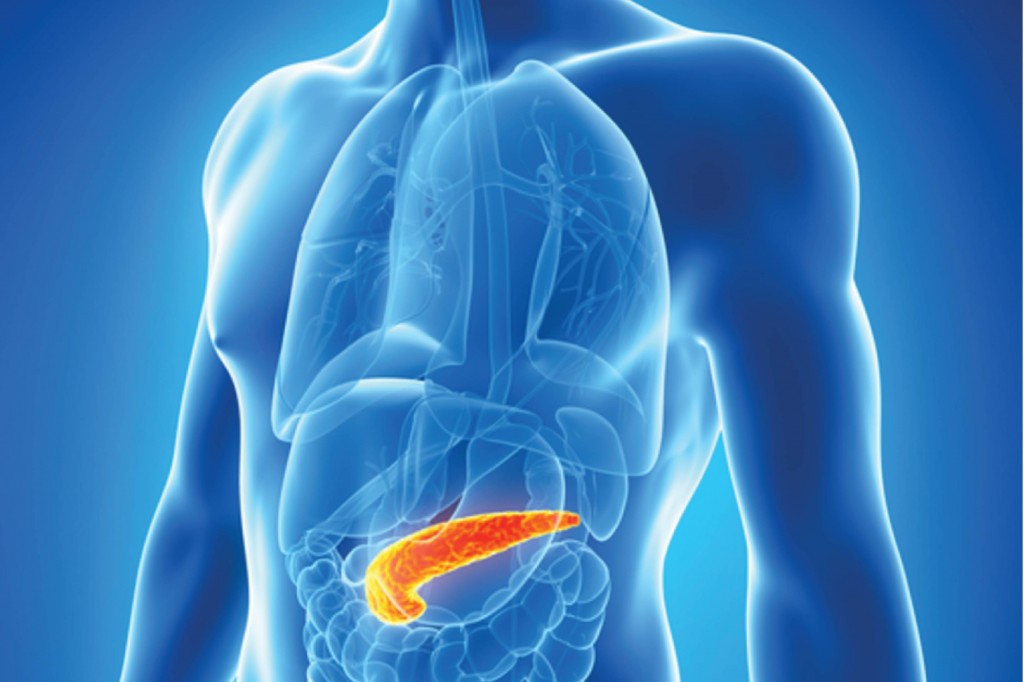

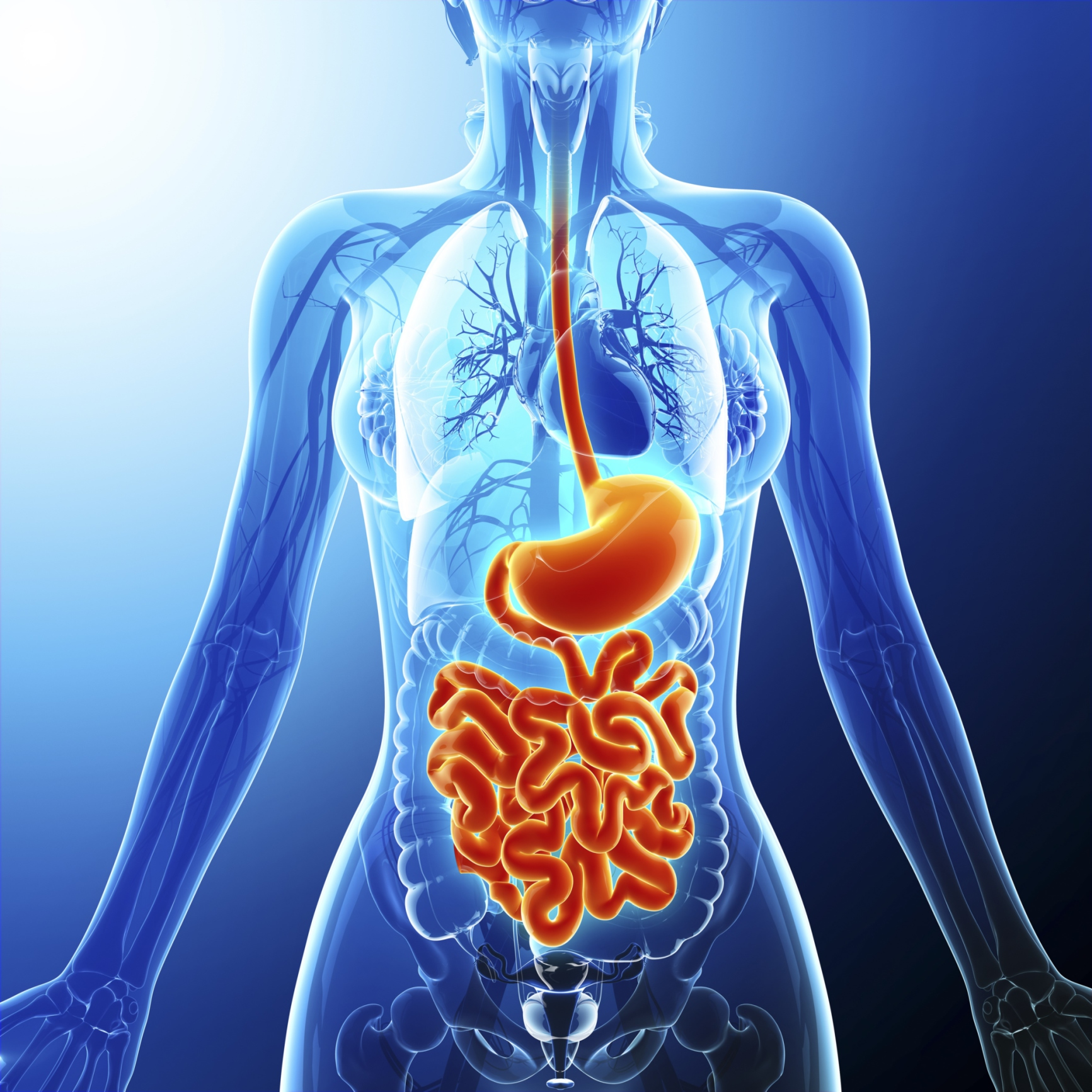

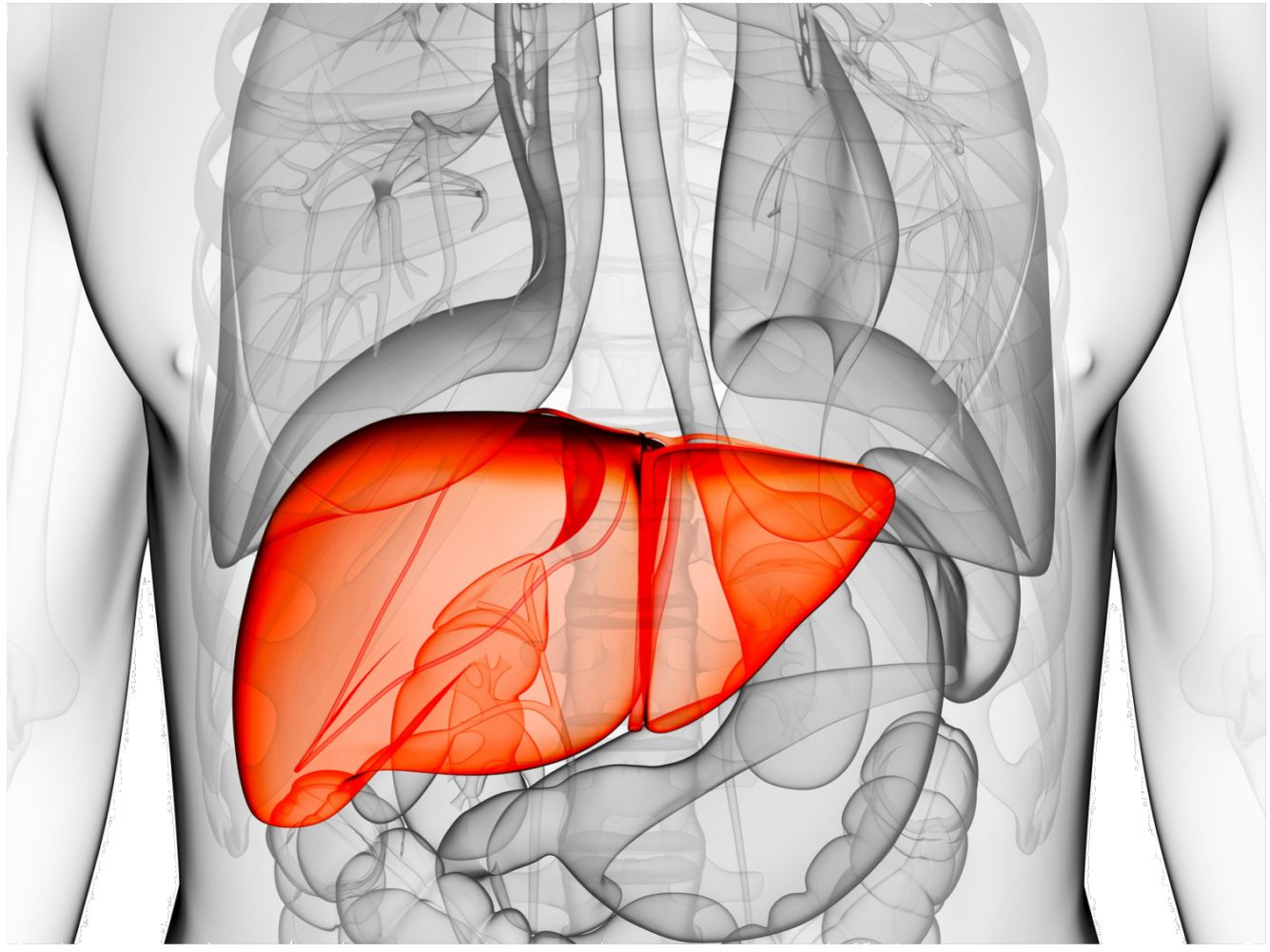

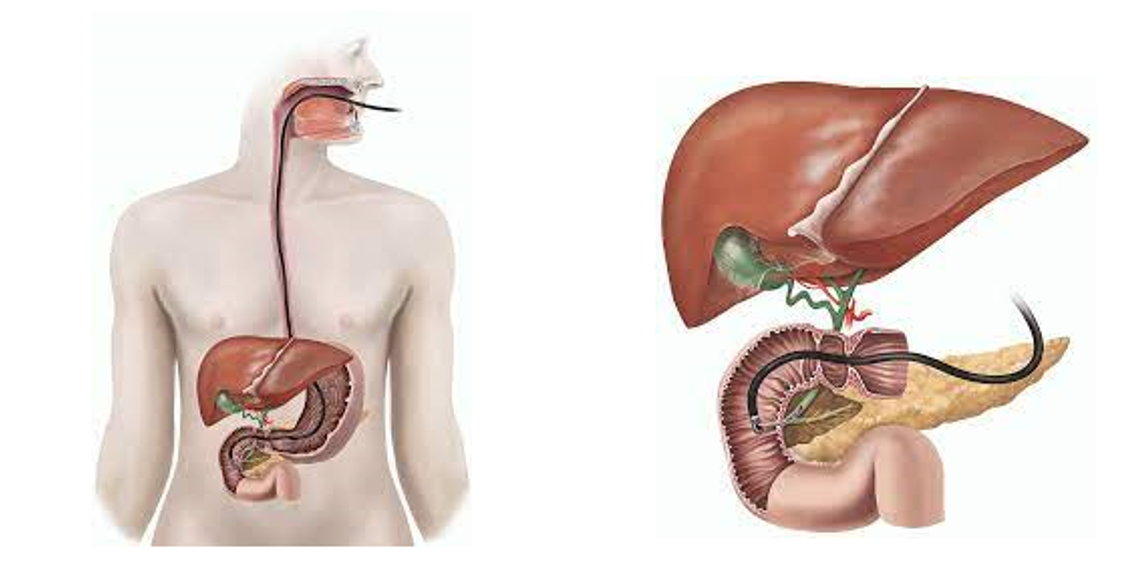

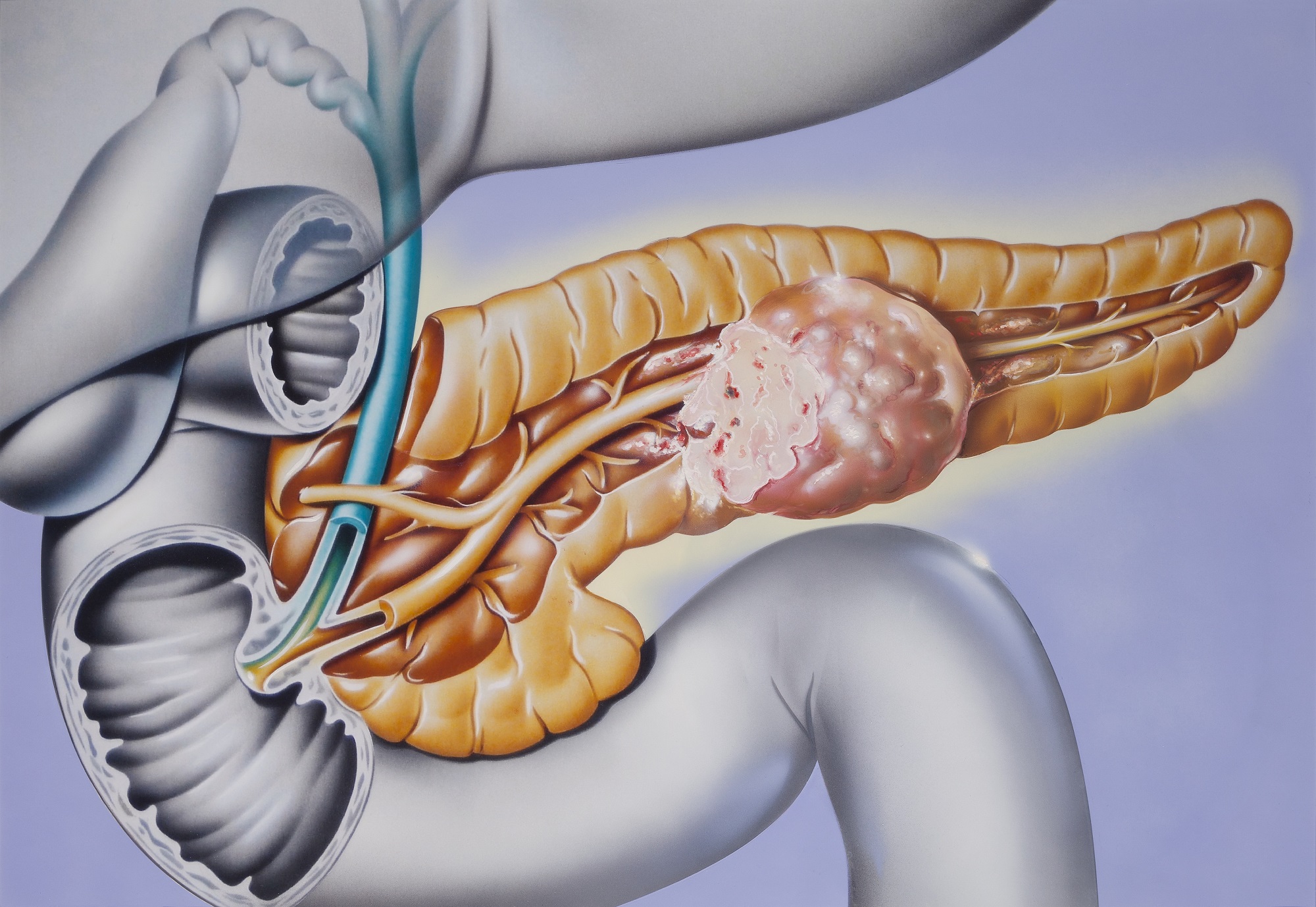

In order to maintain safe levels of glucose in the blood, beta cells in the pancreas produce insulin. These are known as islet cells. However, when a person has Type 1 diabetes, the beta cells are destroyed by a person's own immune system. In turn, those with Type 1 diabetes must monitor their own insulin levels, and inject themselves with insulin as needed to digest glucose.

The Vertex Pharmaceuticals therapy works by replacing insulin-producing cells that have been destroyed with stem cells that convert into insulin-secreting islet cells.

There are still many unknowns with the trial, such as whether there are adverse effects, and if the therapy lasts a lifetime or needs to be repeated. The trial is also experimenting with dosage and way in which the therapy is administered.

"We're evaluating multiple approaches to deliver the insulin-producing cells, including a transplant approach that requires immunosuppression (the VX-880 program), and a device approach that is intended to protect the transplanted cells from the immune system," Heather Nichols, a spokesperson for Vertex Pharmaceuticals said. Nichols said they hoped to apply for an investigational new drug. "Both approaches use our proprietary, fully differentiated, insulin-producing islet cells," she continued.

The initial results from Shelton shocked diabetes researchers. "It is a remarkable result," Dr. Peter Butler, a diabetes expert at the University of California, Los Angeles, told The New York Times in November. "To be able to reverse diabetes by giving them back the cells they are missing is comparable to the miracle when insulin was first available 100 years ago."

While diabetes can be treated and controlled, and some people may go into remission, no cure currently exists. But thanks to this new treatment using stem cells that produce insulin, a new cure could be possible within the next decade.

Still, there are a few quirks to figure out before stem cell therapy is accessible to everyone. And just because positive results have been reported in one trial participant, as Nichols said, dosing and the way the treatment is administered will differ in the next 15 participants.

"It's difficult to say how close we are to a cure, but the beta cell therapy approaches are certainly very exciting," Dr. Marlon Pragnell, vice president of research and science at the American Diabetes Association said, adding that previously, islet transplants from deceased donors have shown to achieve "insulin independence." Yet there are significant barriers in finding deceased donors available to meet that demand — a problem stem-cell therapy can solve. "The potential to grow large quantities of insulin-producing cells in the laboratory could solve this problem," Pragnell noted. (source)

Pragnell said if researchers are able to demonstrate that these stem-cell approaches are both safe and lead to long-term insulin independence, it would be "transformational."

"There would still be a need for immunosuppressive therapy, but it is conceivable that future gene editing approaches may enable researchers to switch off genes that may cause rejection and/or insert genes that promote the body's acceptance of the transplanted cells," Pragnell said.